PhD candidate Temitope Agbana and his colleague Hai Gong received an award from Edmund Optics last month for their project to diagnose malaria with an adapted smartphone.

Tope Agbana MSc. in optical lab at Delft Centre for Systems and Control. (Photo: JW)

Having grown up in Nigeria, Tope Agbana has first-hand experience with one of the most urgent health problems in Sub-Saharan Africa: malaria. If treated well and on time, a patient can recover within a week. But when misdiagnosed as the flu, malaria will continue to develop in the patient with severe and possibly critical consequences.

The correct diagnosis of malaria is crucial. But in practice, it often goes awry, as Agbana explains. “If a child has a fever, for instance, the community health worker may surmise that the patient has malaria just by feeling the child’s temperature with his hand. But all too often the diagnosis is incorrect, and the wrong medication is administered, either because the child’s particular strain of malaria has not been identified, or the kid doesn’t have malaria at all.”

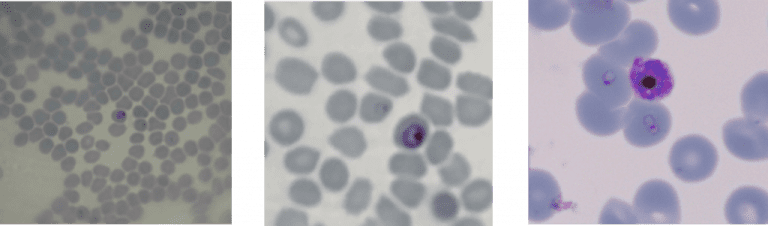

Left: infected sample as seen with smartphone with glass ball lens. Middle: smartphone with glass ball lens and HDR mode with zoom function. Right: same sample under high-end Zeiss microscope.

Under a microscope, malaria shows up in infected red blood cells. A dark spot surrounded by a lighter ring is a tell-tale sign. The World Health Organisation recommends the inspection of 100 microscopy stills of one person’s sample to make a correct diagnosis. So even with a microscope, diagnosing malaria takes time and effort.

At the TU Delft Faculty of Mechanical, Maritime and Materials Engineering (3mE), Professors Michel Verhaegen and Gleb Vdovine employ smart calculation techniques to make high-resolution optical instruments. The group, as part of the Delft Centre for Systems and Control, aims to bring down the costs and complexity of optical instruments like microscopes and telescopes without compromising the performance.

After Tope Agbana had finished his studies at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Sciences (EWI) in 2013, he joined Verhaegen’s group and in 2016 he decided to explore ways for a simple optical solution for malaria detection in Africa. The group formulated the Optical Smart Malaria Diagnost (OSMD), which was then supported by the TU Delft Global Initiative in the form of a PhD research position.

What he shows in the optical lab is a smartphone with a small glass ball in front of the camera lens. The glass ball transforms the smartphone into a modest microscope (8.5 X). The built-in zoom function increases the magnification sufficiently to detect the rings in an infected blood sample.

For the current stage of their work, Tope Agbana and Hai Gong received the Silver Edmund Optics Educational Award last month. Edmund Optics is a supplier of photonics components. Each year a jury evaluates over 750 applications to select 30 prize-winners for their ‘outstanding optics programmes’.

In fact, it’s still early days for the malaria detection tool. Agbana has plenty of ideas to improve the current set-up. For instance, he’d like to be able to detect infected cells without staining the sample. He is also considering using a fluorescent dye to make detection easier and more reliable. Additionally, he is looking into ways of enlarging the field of vision to reduce the required number of stills.

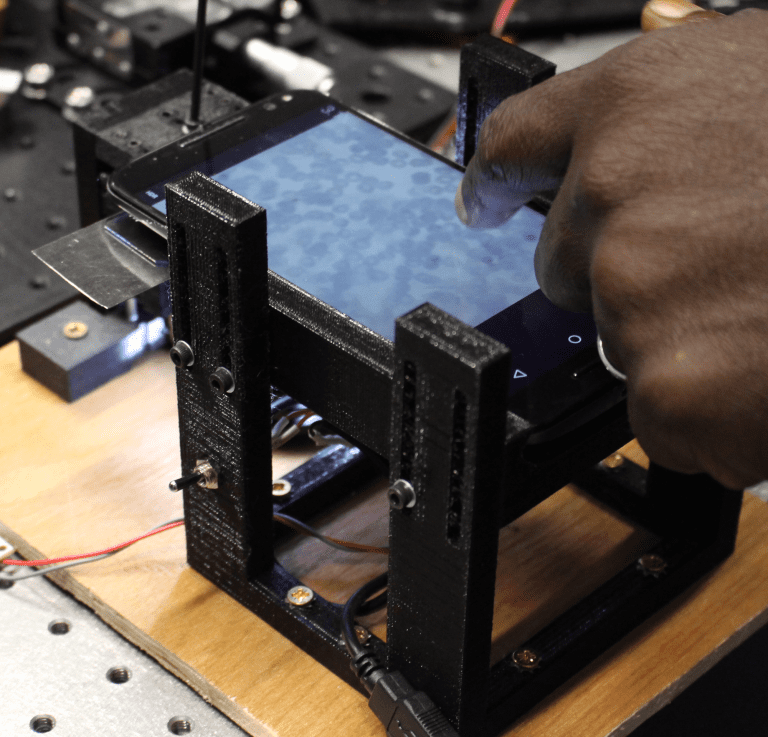

Prototype of user device. (Photo: JW)

Prototype of user device. (Photo: JW)Meanwhile, Agbana keeps his future user in mind: a village chemist in rural Africa. Imagine a small shop in an African village stacked with boxes of pills and potions. People visit the chemist with their complaints and leave with medication. It is the chemist who should be able to reliably diagnose malaria. The technology should be cheap and simple enough to function within this context.

“Of course, the chemist should be able to charge a fee for the diagnosis. Say two euros for one sample. Otherwise, he is better off selling people medicines regardless of their needs.”

A project like this entails much cooperation between entities and individuals. An incomplete list of just some of the institutes and people involved include Professor Maria Yazdanbakhsh‘s malaria research group at Leiden University Medical Centre; Professor Oladepo (public health and development at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria); Dr Jan Carel Diehl‘s Design for Sustainability group at the TU Delft Faculty of Industrial Design and Engineering (IDE); and the TU Delft Global Initiative.

Related articles:

- Diagnose malaria with your 3D printed smartphone case (TU Delta, 15 July 2015)

- Ontwerp TU-alumni kan levens redden (TU Delta, 19 September 2012)

- Using microscope technology on mobile phones to trace malaria quickly and cheaply (TU Delft, 09 November 2017)

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.