Why should dikes and weirs always be made out of steel and concrete? Use rubber-soaked polyamide instead and save a third of the costs, argues Floris van der Ziel.

Floris van der Ziel recently graduated at the faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences (CEG) on an original concept for a ‘movable water barrier for the 21st century’. He likes to call his concept the ‘parachute dam’, because, like a parachute, his weir is a construct that is held in place by ropes and stops the flow of water.

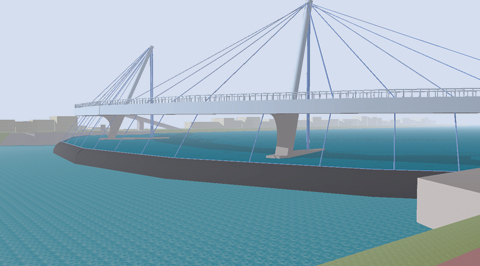

Imagine a wide, horizontally curved bridge that spans a river, as if following a bend in the road. The steel deck is suspended by a series of Dyneema ropes onto two reclining pillars positioned at the inside of the curve. Under this construction, the river flows unimpeded and ship traffic passes unhindered. Except, that is, in cases of emergency, when forecasted high river water levels must be stopped to protect the cities downstream. At such times, the parachute dam will come to the rescue. Hydraulic jacks will start lowering a giant screen from under the bridge into the whirling water below. The force of the water will press the bottom of this heavy rubber screen tightly onto the riverbed. The other end of this rubberised fabric is held upright by dozens of cables attached to the bridge deck, some ten meters higher up. The water level at the inner side of the dam can rise to 4.5 meters higher than downstream. The strongest forces retaining the hydraulic load run along the fabric through a cable located at the bottom of the screen, which is secured to heavy cement foundations situated on the riverbanks. Van der Ziel based his calculations on a 210 meter dam across the Merwede, and concluded that cables made of four, 200 mm Dyneema ropes should be strong enough to cope with the 8,000 tonnes of hydraulic load.

The parachute dam is Van der Ziel’s proposal for the four movable river barriers in water management plan for the water system around Rotterdam and Dordrecht. This ‘Usually Open, Occasionally Closed’ (UOOC) (or Afsluitbare Open Rijnmond) plan aims to provide maximal accessibility to the harbour, while safeguarding this densely populated area from flooding by either the sea from the west or the rivers Rhine and Meuse from the east. The OUOC plan calls for river barriers at Spui, Drecht, Merwede and Lexmond that can be deployed when needed, but which will have to remain in an unobtrusive, resting position most of the time.

Van der Ziel regards concrete and steel weirs as so 20th century. His flexible solution offers many advantages, not least of all that it can be constructed quickly, which is important on a busy waterway. When not in use, the screen is folded under the bridge, so that shipping is not hindered. The (cycle) bridge is an ‘extra’ that stimulates local recreation. The costs are 34 million euro for the bridge and 190 million for the screen, which is about a third cheaper than a steel, movable barrier, Van der Ziel says. What’s more, the screen is not only physically flexible, but it is also adaptable to a changing climate. When in some thirty years time the screen must be replaced, its size can be optimised according to the current conditions.

What then are the chances of one day seeing parachute dams spanning broad Dutch rivers? The idea has been presented previously, in the late 1980s, by professor Han Vrijling, under the name ‘spinnaker dam’, although it was never built, because people feared the screen might fail, allowing the waters to pass over it. Van der Ziel has modified Vrijling’s screen by adding a bridge that will hold the screen in place using dozens of ropes. Still, his supervisor, Ad van der Toorn, doesn’t expect the parachute dam to be constructed on a large scale any time soon. It will first have to be demonstrated as a weir in smaller rivers, he says. There are dozens of suitable locations to construct a parachute dam, but the initiative will have to come from one of the regional water boards. Contractors moreover act conservatively, since most projects nowadays are tendered in design, build & maintenance contracts, which stifles innovation.

Floris van der Ziel was the first CEG student to graduate under the Climate Adaptation Lab (CAL), a joint graduation project of the faculties of CEG and Architecture.

Plutonium is in de wereld gehaald om kernbommen mee te maken en het is verder vrijwel nergens goed voor. Het is giftig, het geeft kankerverwekkende alfastraling af en slechts vijftien kilo van de juiste soort is genoeg voor een bom. ‘De wereld zwemt in plutonium’, schrijft Jeremy Bernstein in zijn monografie ‘Plutonium, a history of the world’s most dangerous element’, ‘De vraag is, wat ermee te doen?’

Het begin van het plutoniumverhaal is onschuldig genoeg. Toen in het begin van de twintigste eeuw eerst röntgenstraling ontdekt werd en vlak daarna radioactiviteit bij uranium, thorium, radium en polonium, rees de vraag of er ook zwaardere elementen zouden bestaan dan uranium (atoomnummer 93 in het periodiek stelsel der elementen). Dat bleef een hypothetische vraag tot de ontdekking van het neutron door Chadwick in 1932. Toen realiseerde men zich al snel dat het neutron uitstekend geschikt was om atoomkernen mee te onderzoeken omdat het door het ontbreken van elektrische lading niet afgestoten zou worden door de positief geladen atoomkern.

De eerste die allerlei elementen met neutronen begon te bestralen, was Enrico Fermi in Rome. Ook uranium werd met neutronen gebombardeerd en door een toevallige ingeving zette Fermi een blok paraffine in de neutronenbundel en zag dat het bestralingseffect enorm toenam. Kennelijk werkten langzame neutronen beter dan snelle. Bij de bestraling van uranium ontstond een element met halfwaardetijd van dertien minuten. Fermi nam aan dat het een nieuw element betrof met atoomnummer 94 (plutonium) of hoger, maar een relatieve buitenstaander (en een vrouw) Ida Noddack suggereerde dat het uraniumatoom wel eens gesplitst kon zijn. Dat buitensporige idee werd vooralsnog genegeerd. Pas toen de Duitse onderzoekers Hahn en Strassman aantoonden dat bij bestraling van uranium barium ontstond (met atoomnummer 56), was atoomsplitsing aangetoond. Men wist uit een van de artikelen van Einstein uit 1905 (E=mc2) dat daarbij grote hoeveelheden energie vrijkomen. En ook dat het volgende element plutonium met atoomnummer 94 erg energiek leek. Werner Heisenberg vertelt in 1942 aan een publiek van vooraanstaande nazi’s: ‘Element 94 is zeer waarschijnlijk, net als uranium-235 (de atoommassa – red.) een explosief met onvoorstelbare kracht. Dit element ontstaat door bestraling van uranium en het is er chemisch van te scheiden.’

Op dat moment was de plutoniumproductie in Amerika al begonnen. Eerst met een cyclotron dat protonen versnelt en daarmee in een blok beryllium een bundel neutronen genereert. In anderhalf jaar tijd werd met twee machines slechts twee milligram plutonium geproduceerd. Later, vanaf 1943, werden kernreactoren ingezet om plutonium te maken. Een deel van het uranium verandert door de neutronenstraling in plutonium. De productie vond voor het grootste deel plaats in Hanford aan de Columbia-rivier. Subtiel ging dat niet en afgebroken brokstukken splijtstofstaven van tot een pond kwamen in de rivier terecht. Maar het was oorlog en men zei dat de Duitsers al bijna een kernbom hadden, dus even niet zeuren nu.

Waarom de Duitsers ondanks hun voorsprong voor de oorlog geen kernbom hebben ontwikkeld is een mooi en spannend verhaal, maar te lang voor hier.

Na de oorlog ging de plutoniumproductie pas echt van start. Vooral in de jaren zestig werden jaarlijks tonnen geproduceerd. En nu zitten we ermee. Hooguit kan het bijgemengd worden in brandstofstaven voor kernreactoren, maar ook dat zet niet echt zoden aan de dijk. En het schijnt relatief duur te zijn. Bernstein: ‘Wat miljoenen heeft gekost om te maken, gaat miljarden kosten om ervan af te komen.’

Emiritus hoogleraar Jeremy Bernstein heeft een mooi compact boekje geschreven over een fascinerende stof. De historische reconstructies zijn nauwgezet en levendig. Toch is Bernstein meer een professor dan een journalist. Zo ruimt hij acht pagina’s in voor de verschillende kristalvormen van plutonium, maar over gezondheidsrisico’s en proliferatie van kernwapens schrijft hij opmerkelijk beknopt. Desondanks een aanrader, zeker voor kernfysici.

Jeremy Bernstein: ‘Plutonium, a history of the world’s most dangerous element’, Joseph Henry Press, Washinton, 2007.

Comments are closed.