Delft researchers received an EU grant to make nanoparticles and ‘super atoms’ by spark discharge.

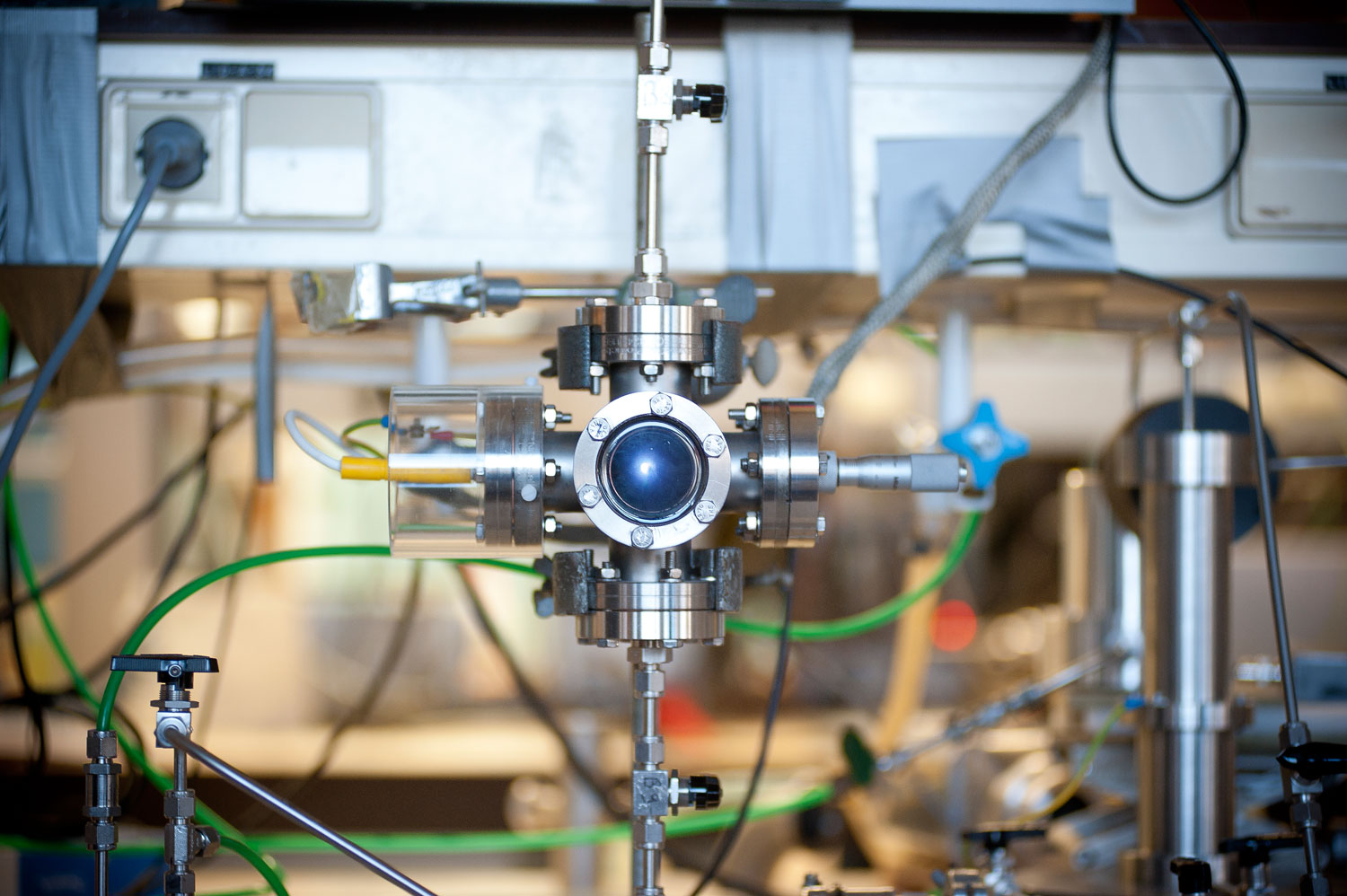

Rapid little flashes of light twinkle in a little glass-topped container surrounded by tubes and pipes.

With each spark between the two magnesium electrodes, PhD student Tobias

Pfeiffer (AS) makes magnesium nanoparticles. These particles could prove useful for storing hydrogen in fuel cells.

“I’m making about a milligram a day of this material. A car needs 80 kilogram of it. At the rate I’m going it will take me centuries to obtain enough for one car”, Pfeiffer says, laughing. “We have to add some zeros to the production speed.”

Speeding up is exactly what he and his promoter, Professor Andreas Schmidt-Ott, are about to do. They are part of a consortium of 20 European research institutes and companies that received an EU grant worth nearly 8 million euros for scaling up this apparatus for nanoparticle production, called the spark generator.

The spark generator was invented in 1988 by Prof. Schmidt-Ott, and improvements are presently being patented by his group. The principle is simple: sparks are generated between two electrodes of a conducting or semiconducting material, and when this occurs, a cloudlet of vapor from the electrode material is formed. As this cloud cools down, the molecules agglomerate and stick together forming nanoparticles.

“With this technique, we can make novel materials ranging from catalysts to battery electrodes,” Prof.

Schmidt-Ott says. “Since we’re able to dose the amount of energy in every spark very precisely, we can generate particles that are all the same size. Another feature is that we can mix different materials.”

One way to speed up the production process is to increase the spark frequency, from the current 500 Hertz to 10,000 or 20,000 Hertz. This is what the TU Delft researchers want to do. Colleagues in Germany, meanwhile, will experiment with putting spark generators in a series.

Industry is primarily interested in the production of nanoparticles. From a fundamental point of view however, Schmidt-Ott believes that the possibility of making inorganic ‘atomic clusters’ is much more interesting.

These clusters of atoms may behave just like solitary atoms, because they have electrons that ‘circle’ the entire cluster. Silver clusters containing 8, 20, or 40 atoms are examples of particularly stable ‘super atoms’, having closed electronic shells.

Prof. Schmidt-Ott believes that it is possible to make atomic clusters with the spark generator that have completely new magnetic, optical, electrical or catalytic properties.

“What we will be getting at in future is the ability to calculate what a cluster with certain desired properties should look like, and, subsequently, one will be able to produce it with the spark generator. It’s an interesting new way of thinking.”

There is an old Ukrainian joke that goes:

– ‘Old man, you drink a lot of vodka, don’t you?’

– ‘Not at all…only when I eat borsch.’

– ‘And how often do you eat borsch?’

– ‘Three times a day.’

Vodka aside, this joke illustrates the relationship most Ukrainians have with this traditional rich vegetable stew: my father remembers a time when borsch was eaten three times a day in a typical village household, and my grandfather had to have it every day for lunch, accepting no substitutes and refusing to acknowledge the existence of any other soups. In fact, borsch has its own niche category in Ukrainian cuisine: never insult borsch by calling it a soup. Borsch is borsch and nothing else. It’s like a Curry in India or a Plov in Azerbaijan: the centerpiece of national cuisine, and there are literally hundreds of ways to make it. An old proverb says that there are as many borsch recipes as there are women in Ukraine: each housewife makes it her own. Vegetarian borsch is typically served as a warm appetizer, while borsch with meat or fish can be a full meal; borsch with mushrooms or beans is typically eaten during the Lent; and borsch with an extra dollop of sour cream for breakfast is an excellent hangover remedy.

Borsch is a very warming and filling dish, but very healthy at the same time as it mostly consists of vegetables. It is cooked in the tradition of family-style sharing: in gigantic pots, enough to last a large family for several days. And don’t worry about the leftovers—borsch only gets better after a few days, once it has absorbed all of the vegetable flavors, and it will stay good for up to a week. The five basic ingredients—beets, carrots, potatoes, cabbage, and onion—are available at all times of the year, and in a snowy place like Ukraine it can easily turn a boring bland table into a colorful feast. Just imagine, you come home from the freezing cold day of hard work and there waiting for you on the table is a plate of warm borsch, with a bit of garlic and a shot of vodka on the side! For those of you drooling in anticipation of making this hearty dish, just go to www.delta.tudelft.nl and this article’s online version for the step-by-step recipe instructions for making my Mama’s superb vegetarian borsch soup!

Borsch recipe

Ingredients:

– 2-3 large beetroots, whole

– 2 large carrots, finely chopped

– 2 onions, finely chopped

– 5 potatoes, cut in 2-cm cubes

– 1⁄2 head of white cabbage, finely chopped

– A can of chopped tomatoes (or 3-4 fresh ones)

– A small can of tomato puree

– 5-7 cloves of garlic, finely chopped or crushed

– Large bunch of dill

– Bay leaves

– A bit of olive oil

– Salt and pepper to taste

– Sour cream to serve

To cook borsch, begin by boiling the beets, skins and all, in a separate small pot. Simmer the carrots and onions on a low heat in a frying pan with a bit of olive oil, just until the onions are translucent. Meanwhile, fill a 5-liter pot about halfway with water and put it on a high heat, dropping in a few bay leaves. Add the chopped cabbage and potatoes to the water. Mix a tin of tomato paste with a cold glass of water and add that as well, along with the chopped tomatoes and garlic. When the beetroots are cooked (a knife goes through them easily), peel and coarsely grate them, and along with the simmered carrots and onions, combine them with the stew. Add salt and pepper to taste, then chop a large bunch of dill and throw it in as a final touch. Bring everything to the boil and turn off the heat. If your hunger can wait, let the borsch stand for a few hours, to allow it to absorb all of the flavors of the vegetables. Serve it hot, with a dollop of sour cream optional.

Comments are closed.