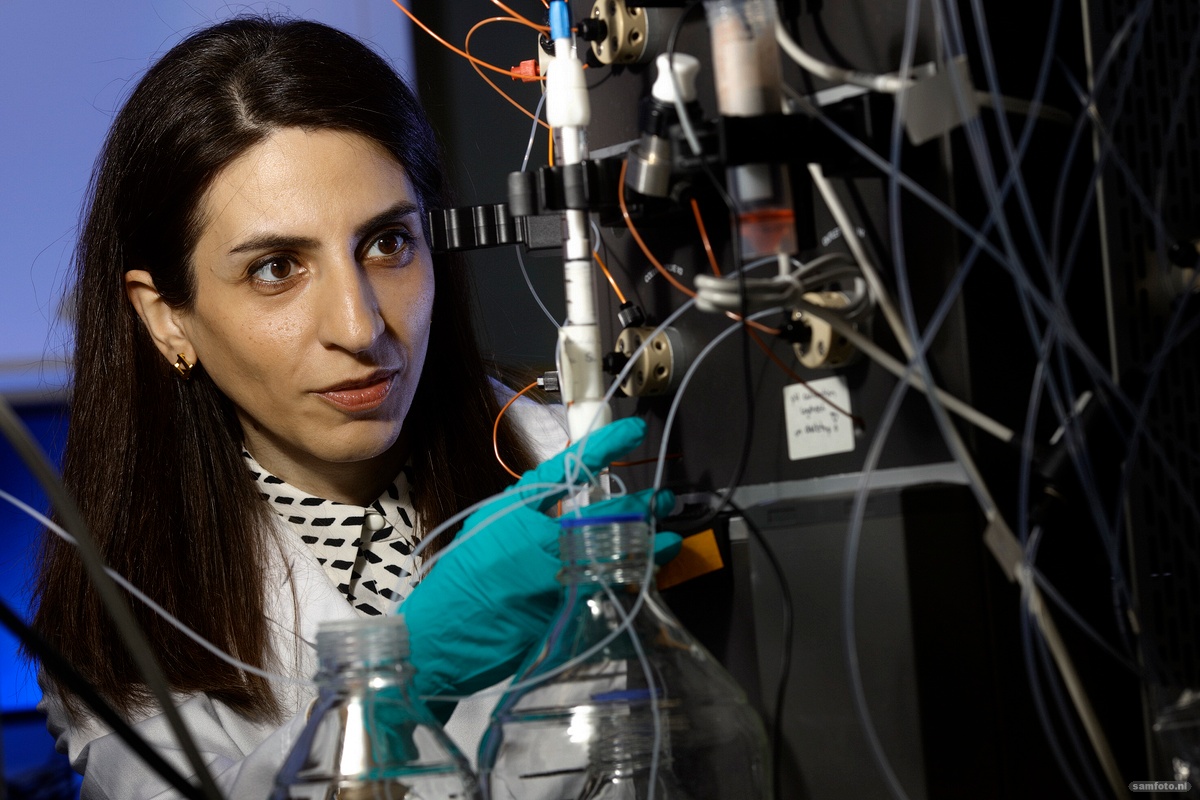

Brewers get more control over the taste of their beers by using a process called adsorption. Dr Shima Saffarionpour pioneered the technology for Heineken.

Dr Shima Saffarionpour with an adsorption column (Photo: Sam Rentmeester)

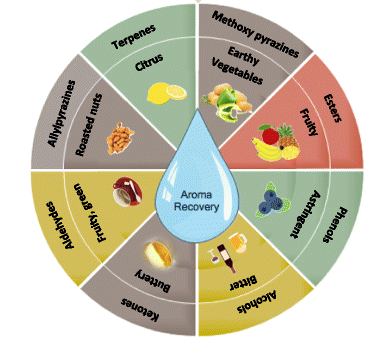

Hoppy, sweet, cherry, and coffee. Clove, banana, succulent plum, and crisp apple. There is no shortage of terms for describing the flavours in beers. Although process engineers will refer to them as esters, ketones, phenols, alcohols, and the like. Some of these are welcome and characteristic. Others, like sulphur or buttery, are substances that brewers would like to get rid of. Regardless of the personal appreciation, brewers want maximum control over their product: a consistency of flavours throughout seasons and years.

Beer manufacturer Heineken teamed up with the Institute for Sustainable Process Technology (ISPT), TU Delft and Wageningen University in a project on the selective removal and recovery of tastes and smells from beer. In the introduction of her thesis, Dr Saffarionpour, who worked on the project during her PhD research, writes: ‘The aim of the project is to come up with tailored beer profile compositions which are no longer limited by yeast capabilities, and with non-alcoholic beer that matches the flavour profile of normal beer.’

Flavour recovery

The technology of choice is adsorption, or the binding of compounds to a prepared surface in a reactor. ‘Adsorption is identified as one of the available techniques for flavour recovery with high potential for use in combination with thermal processing’, writes Saffarianpour. Heating makes volatile substances evaporate, she explains. Using adsorption to bind these substances before heating and adding them back afterwards is a tested way of retaining flavour despite processing.

Alcohol

A complication in adsorption is the presence of alcohol. For alcohol-free beer for example, the industry wants to maintain the original flavours and only take out the alcohol. Saffarianpour has shown that with adequate timing and the right substances (called ‘resins’), a number of substances can indeed be separated from ethanol (‘alcohol’) by adsorption. The process requires rather precise timing. The difference in the time it takes for various substances to bind to the filters coupled with the time that the filter takes to become saturated (breakthrough time), cause the composition of the outflow to vary.

Industry

Adsorption can be used in the brewing industry to remove components in the production process. The more advanced application that Saffarionpour worked on, namely to influence and change flavour profiles, is still far from industrial application, says Eric Brouwer, senior scientist with Heineken.

Brouwer, who was member of the PhD commission, underlines the complexity of selective adsorption in practice, due to thousands of components in the mixture. Saffarionpour did her experiments with a model system with five components.

According to Brouwer, the next nearest application of adsorption in industry could be the recovery of flavours from the distillate in the production of alcohol-free beer.

- Shima Saffarionpour, Tuning flavor-active components, PhD supervisors Dr Marcel Ottens and Professor Luuk van der Wielen, 26 November 2018

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.