By modeling the soft tissue biomechanics and the suspension of the human eye Dr. Sander Schutte believes surgery to correct strabismus, or the condition of crossed eyes, can be improved.

As an engineer “knowing next to nothing about the biology of vision”, Schutte was stunned when he first started studying soft tissue biomechanics and the suspension of the human eye. The human eye has no system with pulleys behind it. Yet it turns in almost pure rotation. “The rotation of the eye is achieved by interacting soft tissues only. It is the orbital fat which prevents the eye muscles to move sideways during eye movements. It’s fascinating”, the researcher says.

The ultimate goal of Schutte’s work is to help improve the surgery for correcting strabismus. Last month the scientist defended his thesis entitled ‘The improvement of strabismus surgery, the role of the suspension of the human eye’. He performed his research in close collaboration with ophthalmologists and scientists from the Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam.

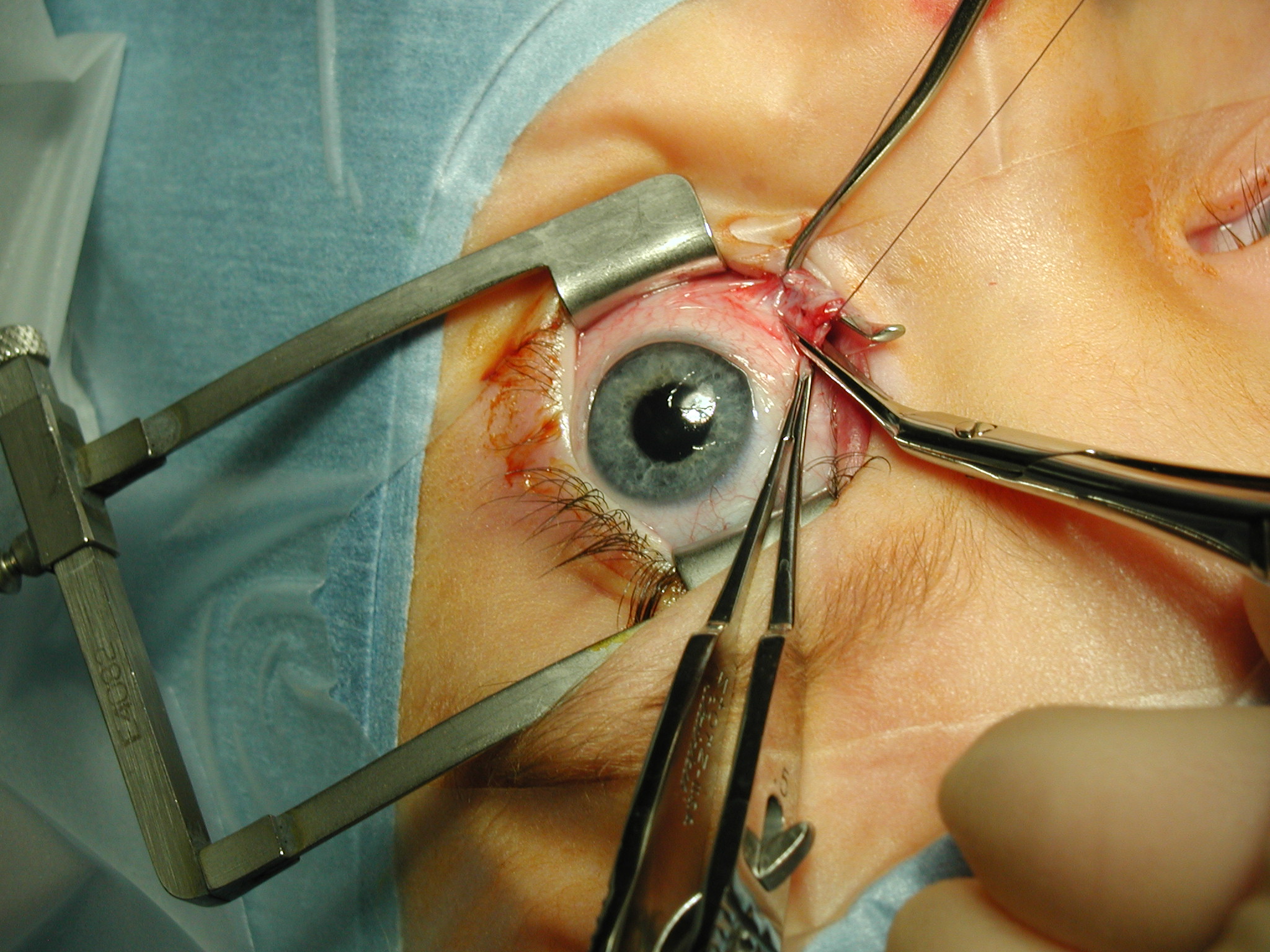

Strabismus occurs in approximately 4 percent of the population and is usually corrected by surgery. In the Netherlands, this operation is performed approximately 150 times per week, mostly on young children. Most of these operations are corrections of horizontal eye position by relocating the insertion of one eye muscle on the eye a few millimeters backwards.

“It is a very straightforward operation requiring no more than a ruler, a pair of scissors and thread and a needle. And the procedure has hardly changed since it was first devised in the nineteenth century”, says Schutte.

These surgeries could however be substantially improved. About twenty percent of all patients need a reoperation because their strabismus was over or under corrected. One cause of this error is the fact that the anatomy and physiological properties of the eye, the muscles and the orbital fat vary greatly between patients. The effect of a given relocation of the eye muscle insertions may therefore also vary greatly between patients. These factors are currently not taken into account before surgery.

To model the way all the tissues act together, Schutte studied dissected eyes and also a functioning eye of a person suffering from Crouzon syndrome who had bulging eyes and went through surgery. He made CT scans behind the eye to visualize the muscles and orbital fat interacting with one another while the patient was looking in different directions.

Schutte also measured the mechanical behavior of the orbital fat of students with an MRI scanner. Combined with his finite element model this type of MRI data could help surgeons to much better predict the right muscle insertion location. Unfortunately MRI is still too expensive to perform on all patients before surgery. “But it is becoming cheaper every year”, says Schutte.

Another cause of error in surgery is the measurement of the angle of strabismus which is usually done by orthoptists with a so called prism cover test. About a third of all reoperations are a result of inaccuracies in the measurements of the angle resulting from these tests, or so Schutte also found during his research.

To tackle this problem Delft researchers amongst whom Schutte together with colleagues from the Erasmuc MC devised a new measuring technique which is less prone to human error. It is designed especially for young children. Strabismus is especially hard to measure on toddlers with the old fashioned technique because they have to cooperate for several minutes.

The possible solution is called Delft Assessment Instrument for Strabismus in Young Children (DAISY), a system that allows for unrestrained head movements by the mean of a triple camera vision system that simultaneously estimates the head rotation and the eye pose. A prototype was built and seems promising. Next year TU Delft and the Erasmus MC, who have a patent on this technique, will have a second prototype built by a company specialized in eye tracking devices called Chronos Vision in Berlin. After that the road is paved for clinical trials.

Comments are closed.