A 3,500 year old ceremonial sword was scanned with neutrons at the TU Delft reactor. The outcome of the collaboration with the Leiden museum is beautiful and puzzling.

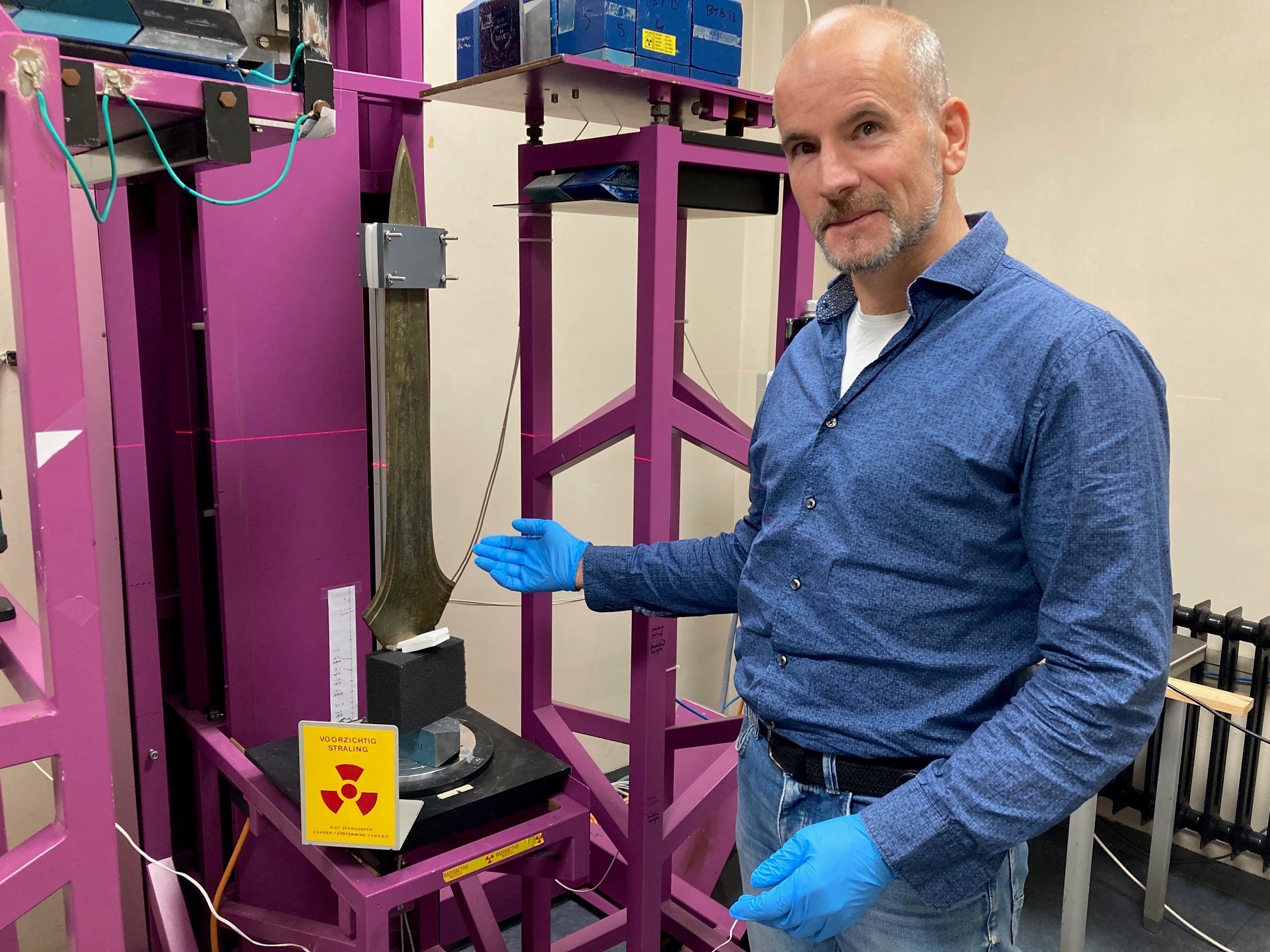

In the basement of the reactor building, Lambert van Eijck measures the radioactivity of a Bronze Age sword. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

Next to the nuclear reactor is a labyrinth of corridors and laboratories. Neutron specialist Dr Lambert van Eijck knows his way around blindfolded. After a few swinging doors and right-angled turns, he pulls open a steel door. Stickers warn of radioactivity and fluorescent tubes flash on. Wedged into a man-sized purple steel frame is an awkwardly large sword. It weighs three kilograms, is 70 centimetres long, and it is here ‘cooling down’, Van Eijck (Faculty of Applied Sciences, AS) says.

Not literally, because it is no warmer than its surroundings, but it is giving off gamma radiation. The neutron irradiation from the nuclear reactor has made it radioactive. Neutron imaging of historical metal objects has become a new specialism of the Reactor Institute Delft (RID). Van Eijck and his team had previously scanned a Van Leeuwenhoek microscope from the Boerhaave Museum. Over the course of several weeks, the gamma radiation will decrease after which the sword can be returned to the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden.

Ceremony

“It is a very important Bronze Age object, the period between 2,000 and 800 before Christ,” says Prof. Luc Amkreutz, Curator of Prehistory at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden and Professor of Public Archaeology at Leiden University. “It is a top European object, of which only six have been found in the whole of Europe. Two in the Netherlands, two in France and two in England. This sword was found in 1896 on a stand of birch logs at the edge of a peat bog near Ommerschans as a gift to the gods. This is therefore a symbolic ritual object, an enlargement of a functional item – the sword. It probably served as a symbol of the importance of warriors to society and as a means of communication with the world of gods.”

Schematic view of the measurement setup. (Illustration: Jos Wassink)

In the reactor hall, Van Eijck shows the setup used to screen the sword. It is a steel scaffold in which the sword was sandwiched between a pipe to the reactor core and a neutron camera. During the screening, the sword was rotated around its vertical axis in 500 steps to achieve a three-dimensional reconstruction (tomography). The maximum height of the beam was about 10 centimetres so it took eight shots to image the entire sword.

“In the Bronze Age, warrior castes rose and leaders emerged,” Amkreutz explains. “Swords play an important role in this. The sword was conceived for man-to-man combat and was made in the Bronze Age. Warriorhood had a special place in society and is associated with the elite. Yet you hardly see swords in tombs. It seems as if being a warrior was not tied to a person, but more like something that was temporary and acquired and had to be discarded after some time.”

Tomography

Series of images show an oblique cross-section of a replica. Note the bubbles (black circles) near the tip of the sword. (Photo: RID TU Delft)

The eight sets of 500 images of the Ommerschans sword have not yet been fully processed into a three-dimensional tomography. Van Eijck expects this to be done at the start of 2023. However, it is clear that there are very few air bubbles trapped in the bronze. Earlier, a tomography was done of a replica (see above) cast by state-of-the-art means. That sword is full of bubbles, especially at the tip. The sword from Ommerschans has far fewer of them.

“That is a first sign that the casting process was done with enormous care,” says Amkreutz. “You don’t want air bubbles in bronze as it weakens the sword and bubbles on the surface produce holes. We can only conclude that the modern replica is a lot worse than what they did three thousand years ago. We have lost that craftsmanship.”

Fingerprint

The neutron beam turns objects radioactive. Excited atomic nuclei return to their ground state, emitting gamma radiation in the process. That process is called ‘cooling’. The good news is that different elements and isotopes (same element, different atomic mass) have their own characteristic gamma wavelengths that become visible as ‘peaks’ in the spectrum, and also have their own half-lives. This spreads the radiation over time.

“At first you see mainly tin-125 and copper-66,” Van Eijck explains. “That’s gone after half an hour. Then comes copper-64. Then the trace elements like arsenic, zinc, antimony or indium show up.” Gamma spectroscopy thus presents a kind of fingerprint of the bronze from which its provenance can be deduced.

Luc Amkreutz thinks that ceremonial swords like these played a role between tribes, gods and trade routes. (Photo: National Museum of Antiquities, RMO)

Amkreutz says that “Gamma spectroscopy gives us information about the material composition of the sword and about the composition of the bronze (an alloy of copper and tin, JW), such as about the ratio of copper to tin. We know that the six swords found in Europe contain a lot of tin, making them shine like bright silvery gold. They also contain trace elements that may indicate where the bronze may have come from. It seems that the same stock of bronze was used for all six swords. That supports the idea that they were made in one place at one time.”

Amkreutz outlines a society 3,500 years ago in which a lively barter trade existed between different regions of central and western Europe and Scandinavia. Amber was probably exchanged for copper, tin, or bronze. Trade routes were very important for prosperity. Archaeologist Amkreutz suspects that ceremonial swords played a role between tribes, gods and nature.

“We think the Ommerschans sword may have been sacrificed at a time when the landscape was changing enormously. It was getting wetter and there was massive peat growth which made access to the area difficult. In time, this may have posed a threat to trade routes. We suspect that the sacrifice of the sword had something to do with that. That it was sacrificed to the gods in the hope of counteracting or controlling the natural changes.”

Further reading:

- We previously covered the neutron scan of a Van Leeuwenhoek microscope (Delta, 2018)

- An article on the opening of the neutron scanner (Delta, 2015)

- Last year, the reactor was re-activated after an extensive overhaul (Delta, 2022)

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.