Scientists see the latest report by the IPCC UN climate commission as a final warning. How does PhD student and climate researcher Sophie de Roda Husman hold out hope?

At the South Pole, ice shelves are loosening rapidly. (Photo: Pxhere.com)

This week saw the release of the IPCC’s, for the time being, latest report on climate change. At more than a thousand pages, the IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report took an almost superhuman effort to summarise more than 8,500 pages of six previous reports in such a way that all governments agree. It will form the basis for the COP 28 climate negotiations later this year in Dubai. In the media, the IPCC report has been received with concern as it shows that the target of a maximum 1.5 degree temperature rise is rapidly moving out of sight. An NOS news report sums up the report in one word: urgency.

Why is that 1.5 degrees is so important? Read that in the text block down below.

Delta phoned climate researcher Sophie de Roda Husman, PhD candidate at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences. She uses satellite data to study the ice shelves around the South Pole. This week, she is reporting on her work on Twitter (in Dutch).

Is the IPCC report important for your research group?

“Yes it is. It is the latest in science. Basically everything we now know about Antarctica and the whole climate system is in it. It is a summary of reports that have come out in recent years, with a separate section for policymakers which contains everything nicely, concretely and concisely. For now, this will be the last IPCC report until 2030.”

Why? We are in the midst of climate change.

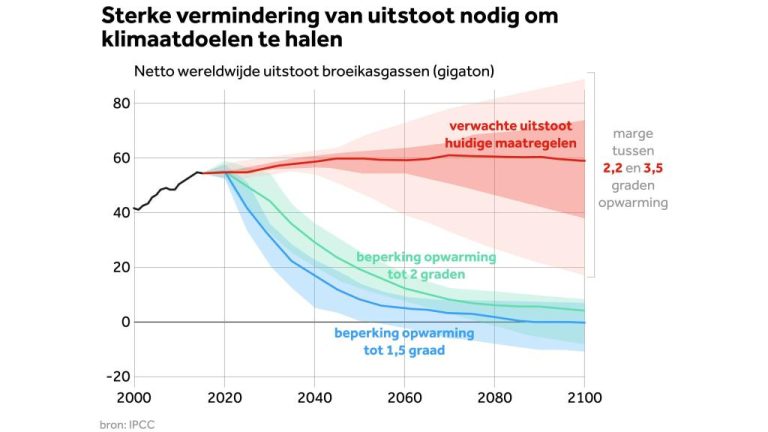

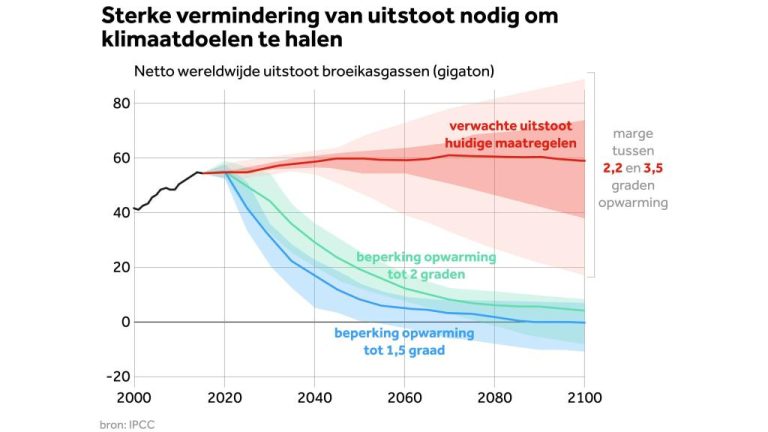

“When the IPCC started in 1988, there was really a lot we didn’t know about how the climate works. Now there is a consensus that we know the most important things, including what it will take to stay under the 1.5 degree temperature rise. The science is out, but the decisions have yet to be made. The thought and perhaps the fear of many scientists is that this report is the last resort to stay below that 1.5 degrees. Before the next IPCC report in 2030, emissions must be reduced dramatically if we are to stay below that.”

(Graphics: IPCC)

What needs to be done?

“That’s pretty clear in the report. It is no longer down to knowledge or technology, because we have them. If there is anything positive in the IPCC report it is that we know how to stay below that 1.5 degrees. It is now about implementation and also about money. The IPCC report says that for a low-carbon society, we need to invest three to six times more in green energy than we do now.”

So it is a question of investing in green energy. Is it also a matter of giving up luxuries like air travel, car driving and nice long showers?

“Yes indeed. Climate change is a crisis that affects people personally, but there are positive sides to the measures. Switching to sustainable energy, for instance, has a tremendously positive effect on biodiversity, liveability and air quality. A more sustainable lifestyle is also fairer.”

What do you mean by fairer?

“The effects of climate change are unfairly distributed. The countries that have emitted by far the least CO2 have 15 times more fatalities from climate disasters such as storms, droughts and floods.”

‘Scientists and politicians in particular must remain hopeful’

I appreciate your positive outlook, but do you understand that people are getting desperate about the latest IPCC report?

“I understand that, but I think it is important to remain hopeful. Scientists and politicians especially need to remain hopeful. I can imagine that people get despondent that that 1.5 degrees is getting harder and harder to achieve. They think all is lost, but that 1.5 degrees is not a hard limit. With every fraction of a degree that we heat the earth, the frequency, intensity and duration of natural disasters increase. Conversely, then, every fraction of a degree of warming you manage to prevent also helps make disasters less severe.”

You yourself are studying Antarctica for your PhD research. Do you see the manifestation of climate change clearly there?

“The changes in that area are evident. A lot of ice shelves have come loose and drifted away in recent years. A few months back, the Conger ice shelf broke off. There are a number of ice shelves around Antarctica that hold the ice in place. In recent years, large plates have broken off and others have become thinner.”

“My study focusses on melting lakes that can make the ice shelves unstable. You see these increasing, at least in Greenland. There, summer temperatures are sometimes well above zero. I look at Antarctica through satellites because the South Pole is the biggest certain factor in sea level rise projections. We can estimate many of the processes that affect sea level rise reasonably well, such as warming and glacier melt. For Antarctica, the range of uncertainty is huge. I want to try to estimate the effects of climate change a little more accurately.”

How do you stay cheerful?

“Climate change can be depressing, but that will only make you passive. A better future is waiting for us on a silver platter. All we have to do is turn our knowledge into action and we’re there. That’s really how I feel about it. We have already come this far! The IPCC shows that things will be fine if we start adopting all green energy sources now.”

The 1.5 degree global warming target was agreed at the 2015 UN climate summit in Paris. It was a tightening of the previous target of no more than two degrees. The lower limit would particularly protect the most vulnerable people in low-income countries and island states.

UN chief António Gutteres called the 1.5 degrees “a point of no return”, which over time gave the target an apocalyptic connotation. Despite all the pledges, with the exception of the Covid period, annual global CO2 emissions have only increased. As a result, as early as 2033, there will be so much greenhouse gas in the air that the 1.5 temperature rise will be reached. Temperature trends also point to the year 2033.

Will that be the end of the world? ‘It is not the case that at 1.5 degrees nothing happens, and at 1.6 suddenly everything happens’, wrote meteorologist Peter Kuipers Munneke recently in the Dutch newspaper NRC. ‘However, weather extremes will get worse between 1.5 and two degrees of global warming. Parts of the ice caps on Greenland and in Antarctica will melt irreversibly, and we will face many metres of sea level rise over hundreds to thousands of years.’

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.