After five years of research, Swiss scientists and TU Delft’s Lukas van den Heuvel are the first to describe the brain circuits recruited to attenuate old fear memories.

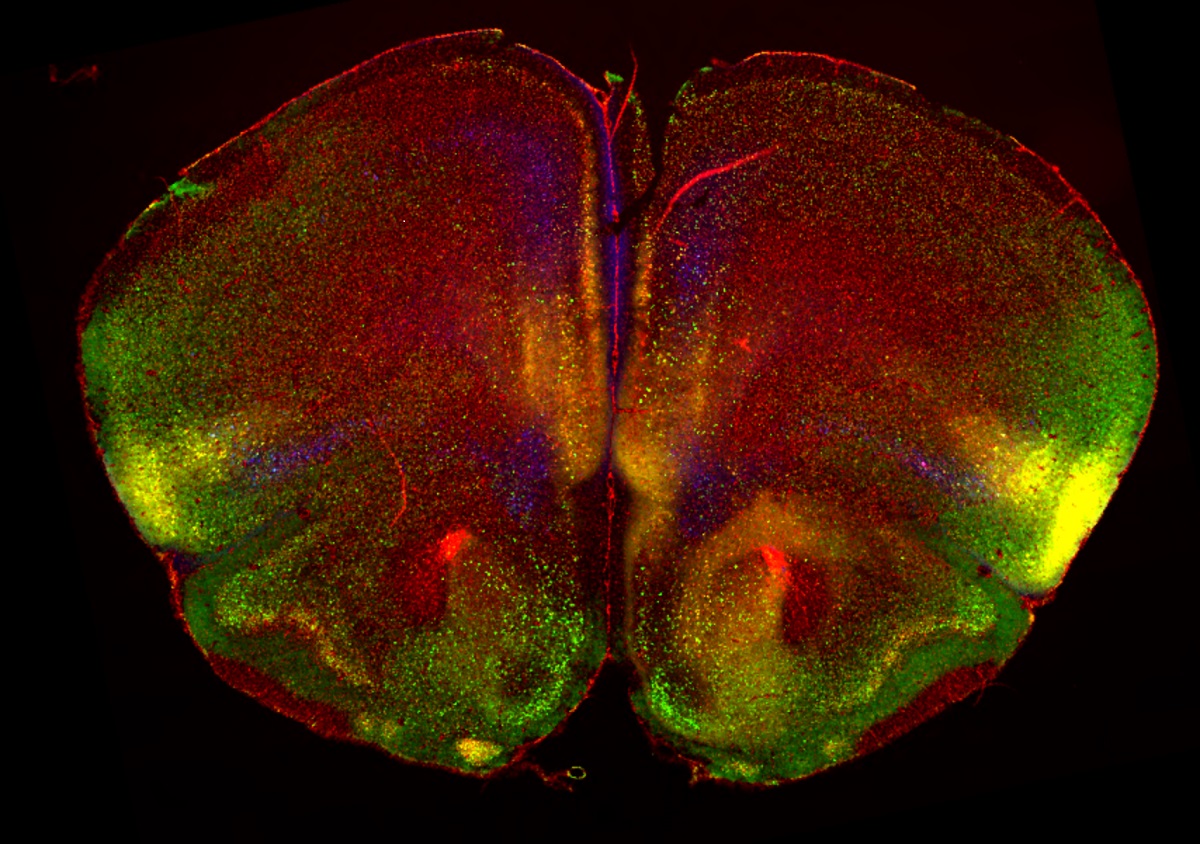

Cross section of the cerebral cortex of a mouse. (Photo: Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne)

Traumatic experiences can result in enduring memories of fear. Exposure therapy is a common treatment to overcome trauma by letting patients to some extent revive the traumatic experience with the help of photos, videos or by letting them rekindle the story. By doing so in a safe environment, the brain learns that danger no longer lurks.

This month in Nature Neuroscience, scientists from the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, amongst whom Lukas van den Heuvel, who now works at TU Delft, showed that the neural mechanisms involved in overcoming fear differ depending on the age of the traumatic memory. Or at least they do in mice.

It is hoped that subsequent research will show the extent to which the findings translate to humans. The discovery may partly explain the reason why exposure therapy is less successful if the traumatic experience occurred a long time ago.

Pavlovian fear conditioning

In the experiments, mice underwent ‘Pavlovian fear conditioning’, in which they received an electric shock from the ground. Traumatised mice express fear by freezing, but after the therapy (after the mice had gotten used to the cage in which they had previously been given electric shocks), the mice regained confidence and normal mobility. One group of mice received therapy one day after the trauma, while another group received therapy 30 days later.

The scientists determined which brain circuits were active in both groups of mice. They found that a direct cortico-amygdala pathway was active one day following the trauma. After 30 days, an indirect pathway was active, one that was rooted in the nucleus reuniens, which is situated deep inside the brain/thalamus.

“We found this out by examining the mouse brains under a microscope,” says Van den Heuvel, who now works at the TU Delft Quantitative Neurobiology Lab. “The presence of certain proteins indicates which neuronal cells were active during the therapy.”

‘This is newly explored territory’

“This is newly explored territory. It is the first time that a brain circuit underlying the attenuation of long-term fear memories has been established experimentally in mice,” he says. “In most studies, mice brains are studied one day after the trauma, mostly for practical reasons I think. Waiting for a month before inspecting your mouse is a long time. But the Swiss lab did it, and it is one of the reasons this project took so long to finalise.”

Turning this recent discovery into therapy for people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder or other long-term traumatic experiences remains a challenge. In collaboration with a partner institute in the Netherlands, the Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, the Swiss scientists have the approval to study similar brain mechanisms in humans.

Van den Heuvel is now involved in a second follow-up project. Using new, brain-wide analysis techniques he is zooming in on other regions in the brain that may play a role in the attenuation of traumatic experiences.

Silva et al. ‘A thalamo-amygdalar circuit underlying the extinction of remote fear memories’. Nature Neuroscience (2021). Access the original scientific publication here.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

tomas.vandijk@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.