The idea to connect the TU with genomic centres via dedicated glass fibres won first prize at last year’s Surfnet ‘Enlighten Your Research 3’ competition.

“Now we’ve got a ten gigabit per second connection for each university, which serves the transport of scientific data but also students reading news sites. Consequently, you’re never sure what capacity is available,” Jan Bot (MSc – EEMCS) explains, regarding the need for dedicated glass fibre connections, called lightpaths, for the exchange of genomic data. His proposal, titled ‘Next generation networking for next generation sequencing’, was awarded first prize at the ‘Enlighten Your Research 3’ (EYR3) competition, organized by Surfnet, the academic internet provider, on 7 December 2011. Bot’s proposal entails a network of lightpaths between the TU and several other institutes: AMC, University of Groningen, Hubrecht laboratory, LUMC, VU Amsterdam, Wageningen University, Beijing Genomic s Institute in Hong Kong and Complete Genomics in California. The last two connections are specialized sequencing companies. “Blood in, bits out,” Bot says.

Bioinformatics means data, lots of data, although less then particle physics. A human genome with 23,000 genes in the current industry standard measures about 300 gigabyte. It takes a single sequencing machine a few days to sequence all the DNA fragments, after which a computer needs about a week to stitch the entire genome together. In practice, these tasks are sped up by parallel processing or by using supercomputers. Up until now, however, research samples are flown to sequencing plants, and then couriers like FedEx or UPS bring the hard disks back. Sending the data by internet or via a cloud is not powerful enough, nor is it secure.

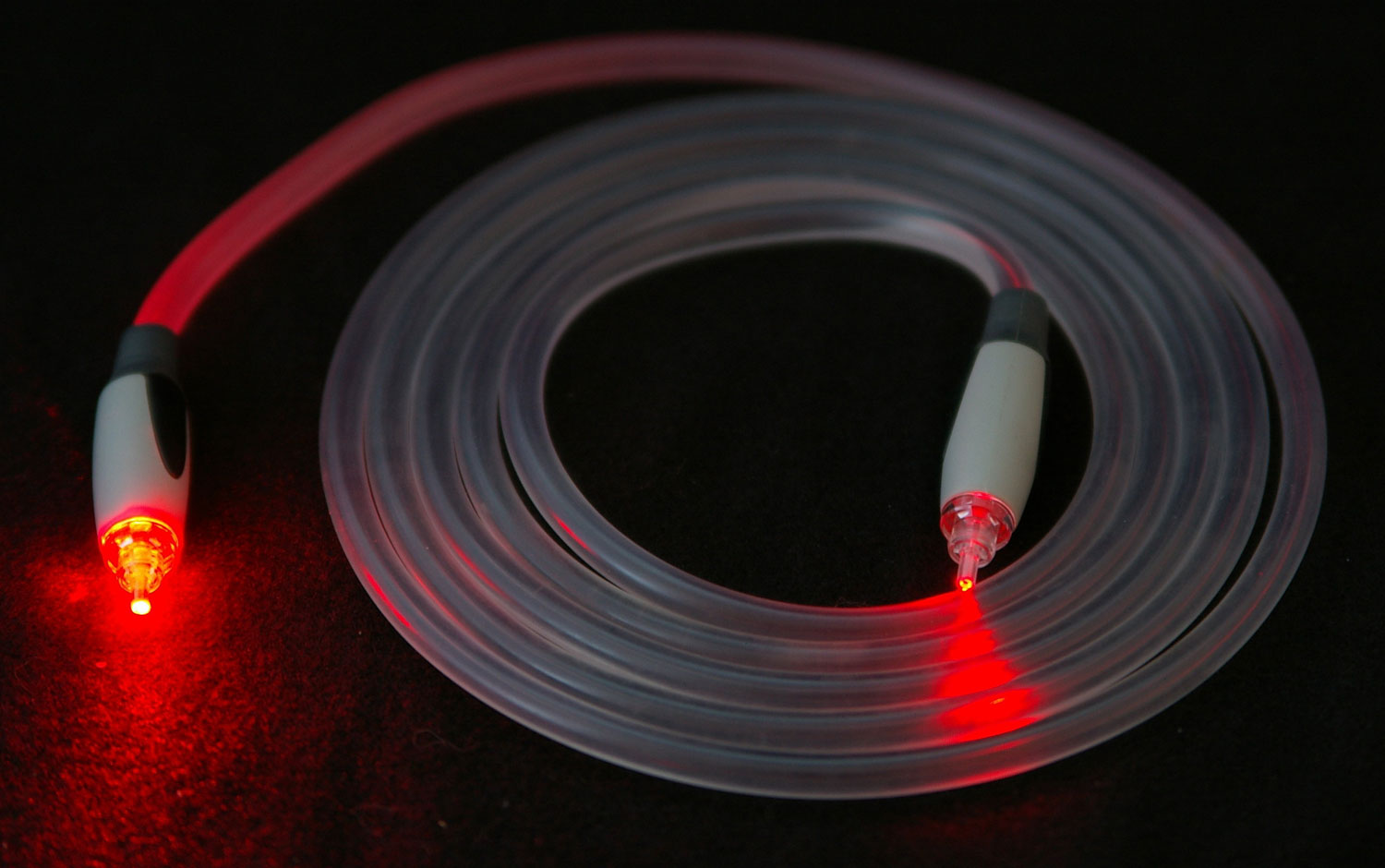

Bot expects the genomic optical network to be operational within a year, after which the exchange of bioinformatics data will be both easier and more secure, since a light path is essentially one continuous fibre without side-branches.

EYR3’s second prize was also awarded to a TU Delft project led by Dr Henri Vrooman (Erasmus MC). He proposed connecting Leiden and Groningen medical centres to the SARA supercomputer and the TU visualization group as an infrastructure for comparing MRI images from population studies.

”A popular, recurring discussion topic during the international ‘Reading the paper with the Rector’ sessions is part-time employment for non-EU students. While international students can legally work up to 10 hours per week here, most in fact find it virtually impossible to find part-time jobs. The Rector’s answer is always the same: studies are difficult, tuition high for non-EU students, the university is concerned that part-time jobs will take away from the students’ study time. Okay, but is the Rector also worried that some of his students must illegally work longer hours in poor conditions for little pay because they don’t have alternatives?

Dutch immigration laws make it hard for non-EU students to find legal work: the 10-hour working permit is given to the employer, not the student, the application process long and tedious, and permits given for just one year. Indeed, whenever the question of non-EU student employment on campus comes up, TU Delft takes the ‘our hands are tied/blame the IND policy’ approach. But is there really nothing one of Holland’s most prestigious, politically and corporately well-connected universities can do to help its international students with part-time employment? Most student assistant or project mentor vacancies don’t require knowledge of Dutch and are well-suited for capable international students. If the minimum 12 hour/week load is re-distributed to fit a 10-hour working schedule, and the job recruitment process begins several weeks earlier, TU Delft could then apply for working permits for non-EU students without any problems. The course schedule and content is known well in advance, so why the February mentors can’t be recruited in September? Giving all students equal employment opportunities will eventually lead to an improved quality of student assistants, and thus to educational quality.

In large student cities like Utrecht, student job agencies supported by the university apply for work permits for international students, helping them find work that doesn’t require Dutch. In contrast, the only student job agency on TU Delft’s campus only accepts Dutch-speaking applicants. TU Delft must pressure such student job agencies to recruit non-Dutch speaking students for jobs that don’t require Dutch, thus giving TU Delft’s international students a powerful, supportive voice in such matters.

A part-time job is part of student life, allowing students to meet new people and gain practical work experience. Moreover, part-time jobs supplement the students’ monthly budgets,

lightening their study debt and/or the cash sink in parental wallets, which for many international students – for whom study grants/loans are limited or nonexistent – means the difference between being able to finish or not finish their studies. The university must stop pretending the problem doesn’t exist and instead help international students gain legal part-time employment during their study years.

Do you agree or disagree with the points raised in this week’s Talking Point? Let us hear your opinion: start or join the discussion in the Comments section below this article.

Comments are closed.