The rise in sea level necessitates an additional dam off the coast, say the inventors of the Haakse Zeedijk. What do they think about this at CiTG?

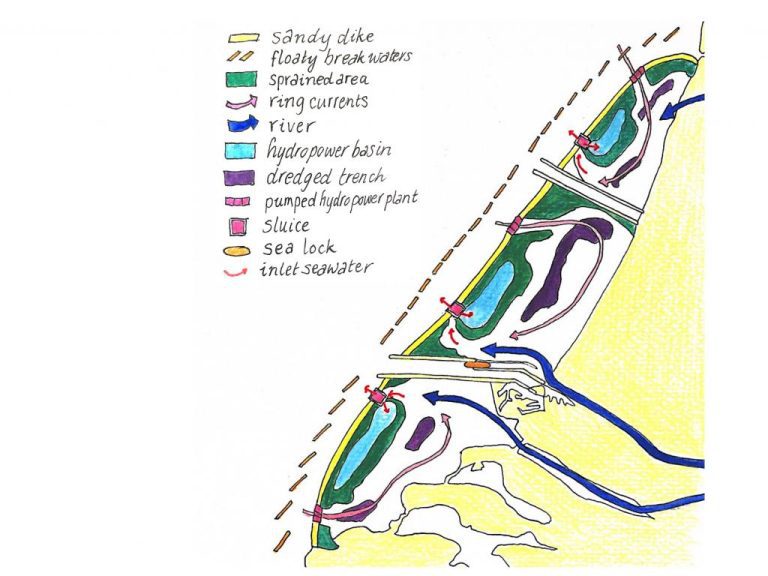

The Haakse Zeedijk protects NW Europa against sea leven rise. (Drawing: Sija van den Beukel)

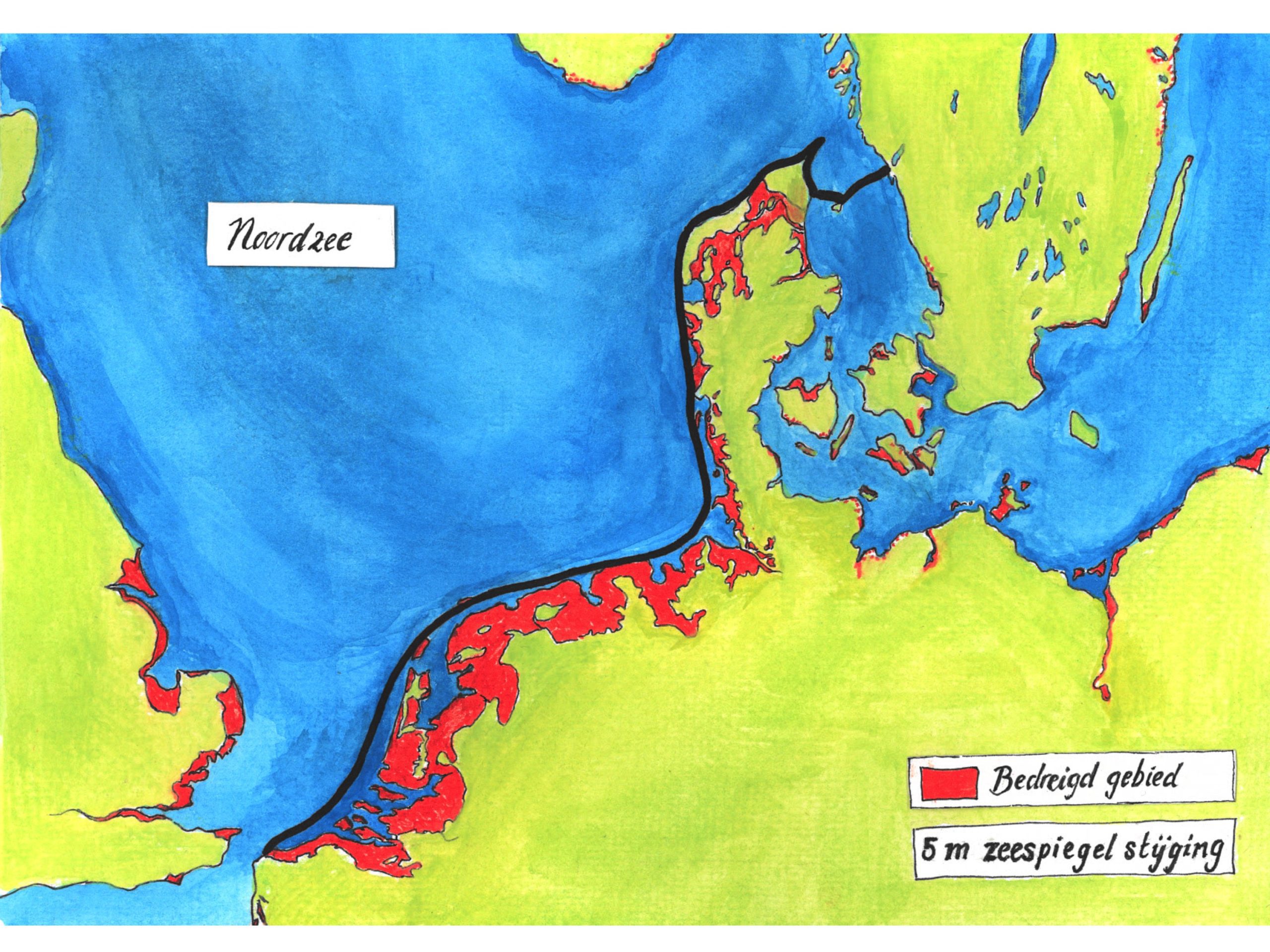

The motivation is clear. ‘If we look three centuries ahead, the period in which the average temperature may not drop, we must be prepared for a five to perhaps eight metre rise in sea level’. This invites large-scale hydraulic engineering plans. There has already been a plan to close the North Sea called the North European Enclosure Dam (NEED). As a less drastic alternative, engineers Rob van den Haak and Dick Butijn designed a plan for a large sand dike off the coast. This should protect the Netherlands, and preferably the whole of Northwest Europe, from the rising sea for the coming centuries. Butijn named the plan De Haakse Zeedijk (DHZ) after his associate who died last year.

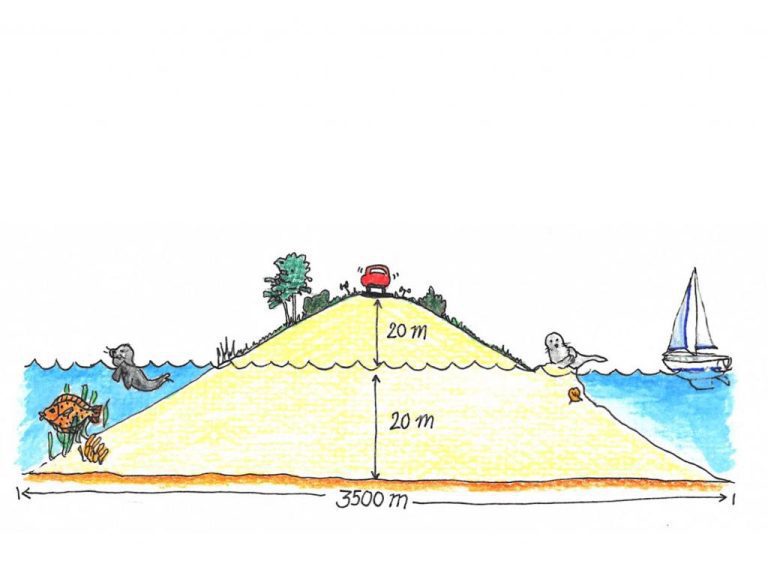

Anatomy of the Haakse Zeedijk. (Illustration: Sija van den Beukel)

In bird’s-eye view, the dike is a 3.5 kilometre wide sand spit that lies 25 kilometres off the coast and rises 20 metres above the current average sea level. Between the dike and the current coast are lagoons from which the sand has been extracted for the dike. There are drainage sluices for the discharge of river water. Inflow sluices on the far side of the spit allows salt water to enter and circulate in the lagoons. In its simplest form, the dam runs from Walcheren to Den Helder, a distance of some 160 kilometres. The European variant parallels the North Sea coast, running for 1,100 km from Calais in France to Skagen in north Denmark and across to Gothenburg in Sweden. What do hydraulic engineers at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences think about this?

Haakse Zeedijk in cross section. (Illustration: Sija van den Beukel)

Appreciation

Dr Bas Hofland (Department of Hydraulic Structures) thinks it is a ‘realistic plan’ as it incorporates nature and shipping, and counters salinisation. “It is an integrated plan, and one of the possible solutions.” Hydraulic Engineer Prof. Wim Uijttewaal appreciates the combination of functions in the plan. The dike is not only a flood defence, but also offers opportunities to build an airport and drinking water basins, and generate energy. The dimensions of the dam, which has a gentle slope of 1:40, is also within the norms. The estimated building cost of EUR 80 billion is on the low side though. Hofland estimates the cost of the sand alone to be around EUR 100 billion (EUR 10 per cubic metre). There are, of course, other questions too.

Waves

Uijttewaal thinks that a structure so far off the coast needs extra protection from wave-driven erosion. Large waves, which mostly dissipate before they reach the beach because of the gradual shallowing of the sea, are still full size 25 kilometres off the coast. The designers have devised floating breakwaters to reduce the wave size, but Hofland does not believe in them. Floating breakwaters barely muffle waves, and even if they do, they quickly break away from their anchors.

Ecology

When the sand is extracted, what happens to the deep holes left behind? According to Uijttewaal they will fill up with cold seawater, and will barely be affected by the circulation in the lagoon. The result will be a bunch of deep dead troughs.

Friesland and Groningen

According to the proposal, the dike only runs up to Den Helder. Uijttewaal questions what will happen to Friesland and Groningen if the sea level does indeed rise by metres. It seems like the authors have forgotten the nort-eastern part of the Netherlands.

Alternatives

Finally, Uijttewaal points to the lack of alternatives. “In design, the first thing we teach students is to explore all the broad options. Then choose one and work it out. I don’t see any weighing up of alternatives here.”

Necessity?

According to Hofland, the authors are raising the alarm a little too soon. They write: ‘The sea level may rise two to three metres this century and five to eight metres the next century’. The International Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) most recent report shows a two to three metre rise in 2200 (rather than 2100), and a 2.5 – 5.5 metre rise in 2300. According to Hofland, we can cope with up to two metres of sea level rise without many additional measures. “We will get through this century with the normal dike rises, replacement of storm-surge barriers, and sand motors. This will probably give us time to study the more drastic measures such as De Haakse Zeedijk.”

New Delta Works

In fact, thinking about new Delta Works has just begun. Uijttewaal considers the Haakse Zeedijk and the NEED North Sea dike as potential solutions, in which DHZ is a lot less drastic for the ecology of the North Sea. He himself is exploring other variants, about which more may be written later.

According to the latest insights from the IPCC, we still have at least 100 years before sea level rise becomes a serious threat. A second coastline is therefore not necessary for the time being. According to Uijttewaal and Hofland, it will be ‘a beautiful subject’ for the next generation of hydraulic engineers.

- Download ‘Europa moet zich voorbereiden op zeespiegelstijging’ as pdf

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.