When the Delft Professor Beijerinck discovered viruses in 1898, they were regarded as a plant disease. It’s much bigger than that, as we have found out.

Historian Dr Lesley Robertson in Beijerinck's reconstructed office. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

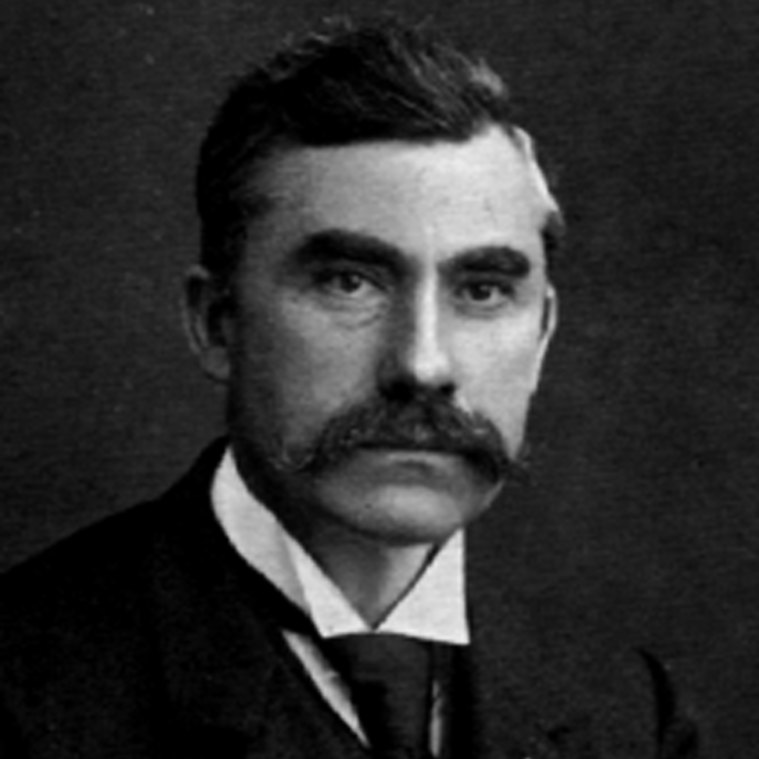

Martinus Willem Beijerinck around the time of the virus discovery. (Photo: Collection TU Delft School of Microbiology)

Martinus Willem Beijerinck around the time of the virus discovery. (Photo: Collection TU Delft School of Microbiology)At the time of the discovery, Martinus Willem Beijerinck was Professor of Biology and Bacteriology at the Polytechnical School in Delft, precursor of the TU Delft. With a background in both chemical engineering and biology, Beijerinck was one of the earliest non-medical microbiologists, and also the founding father of virology.

Tobacco leaves without and with viral infection. (Photo: Collection TU Delft School of Microbiology)

Tobacco leaves without and with viral infection. (Photo: Collection TU Delft School of Microbiology)

A strange disease in tobacco plants, clearly visible from the vesicles forming on the leaves, was the starting point of Beijerinck’s discovery. Plant diseases could have various causes: chemical, bacteriological or fungi. But none of the usual suspects fitted the profile, says historian and microbiologist Dr Lesley Robertson. Beijerinck, she says, was one of three researchers working on what is now known as the tobacco mosaic virus. The others were Russian botanist Dmitri Ivanovsky and agricultural chemist Adolf Mayer from Wageningen University.

Viral mystery

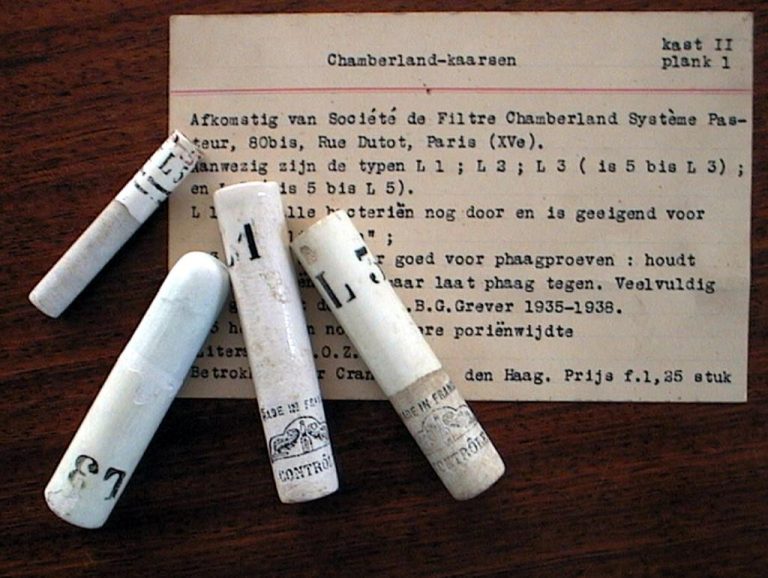

Robertson tells: “There were these two scientists working on it before Beijerinck, it was just that he was the one who got the correct conclusions. But all three of them were looking at the leaves and grinding them up, and looking for bacteria or anything else under the microscope. Then the liquid from the ground leaves was filtered through glass filters that could stop bacteria and the filtrate was painted onto healthy leaves and examined under the microscope. There were no bacteria, but the liquids stayed infectious. Adolf Mayer from Wageningen, was initially convinced it was bacteria causing the disease, but he couldn’t find them. In the end he decided that the agent must be a chemical. For a final confirmation, he asked Beijerinck, who he knew, to have a look.”

Glass filters used in Beijerinck’s experiments. (Photo: Collection TU Delft School of Microbiology)

Glass filters used in Beijerinck’s experiments. (Photo: Collection TU Delft School of Microbiology)

“The Russian, Ivanovsky, had published a paper in 1893″, Robertson continues. “He was also using the filters in the same way and could show that what came out of the filter was infective. However, he was so convinced that it must be bacteria that he decided that, since the filters stopped bacteria, there must have been spores that were much smaller than bacteria that could pass the filters.”

Getting stronger

“Then Beijerinck published his experiments, including two extra steps. He didn’t stop after one filtration, he took the liquid from that and sprayed it on new leaves. When the new leaves got sick, he did it again. He could show that it was getting stronger. Had it been a chemical, it would be getting weaker. So that pushed Mayer’s theory (of a chemical agent) out. It couldn’t be a chemical. With the microscopes they had then, you can see bacterial spores. I’ve done it with Beijerinck’s microscopes. It couldn’t be spores either. They couldn’t cultivate it. Beijerinck was an expert in growing things that were difficult to grow, but nothing grew on the special media he had prepared. That was the big breakthrough. This is why people give Beijerinck the honour of being the first to discover viruses because he realised it was alive and not chemical. He realised it was self- replicating. And he realised through tests that it was not bacterial.”

After the discovery of the virus, Beijerinck got bored and returned to other things. (Photo: Collection TU Delft School of Microbiology)

“The trouble is, he got bored. Because he couldn’t grow it, he couldn’t see it. He could just show that it was there because leaves got sick if he sprayed it on. So he went back to work on other things. With a virus you can’t be sure it’s there, unless you have an electron microscope.”

Virus in view

“These only started coming in the late 1930s. Delft got their first one during World War II, when Jan le Poole’s group at the Applied Physics group developed their own. People don’t seem to have associated the role of viruses in human diseases until they could be identified and the electron microscope played a large part in this. They have different shapes and some don’t look very exciting, just like a long bit of string. Some of them, like the coronavirus, are quite pretty. But they’re all fairly distinct.”

“The role of viruses in human diseases was not so easy to establish. There is no way you could take, for example, liquid from smallpox blisters and see if they infect another human, as you can with plants. People must have been musing about it, but at the time of the discovery of the virus, microbiology was still a bit of a non-subject. It was regarded as a part of botany and as such not directly applicable to animals.”

- Further reading of the TU Delft School of Microbiology or its weblog.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.