The architectural construction of the Israeli state is a distinctly modernist project. This is what Israeli architect Zvi Efrat posed during a lecture held at TU Delft April 22.

Organised by The Berlage, the lecture examined the role architecture played in constructing the Israeli state, from housing units to Brutalist public buildings.

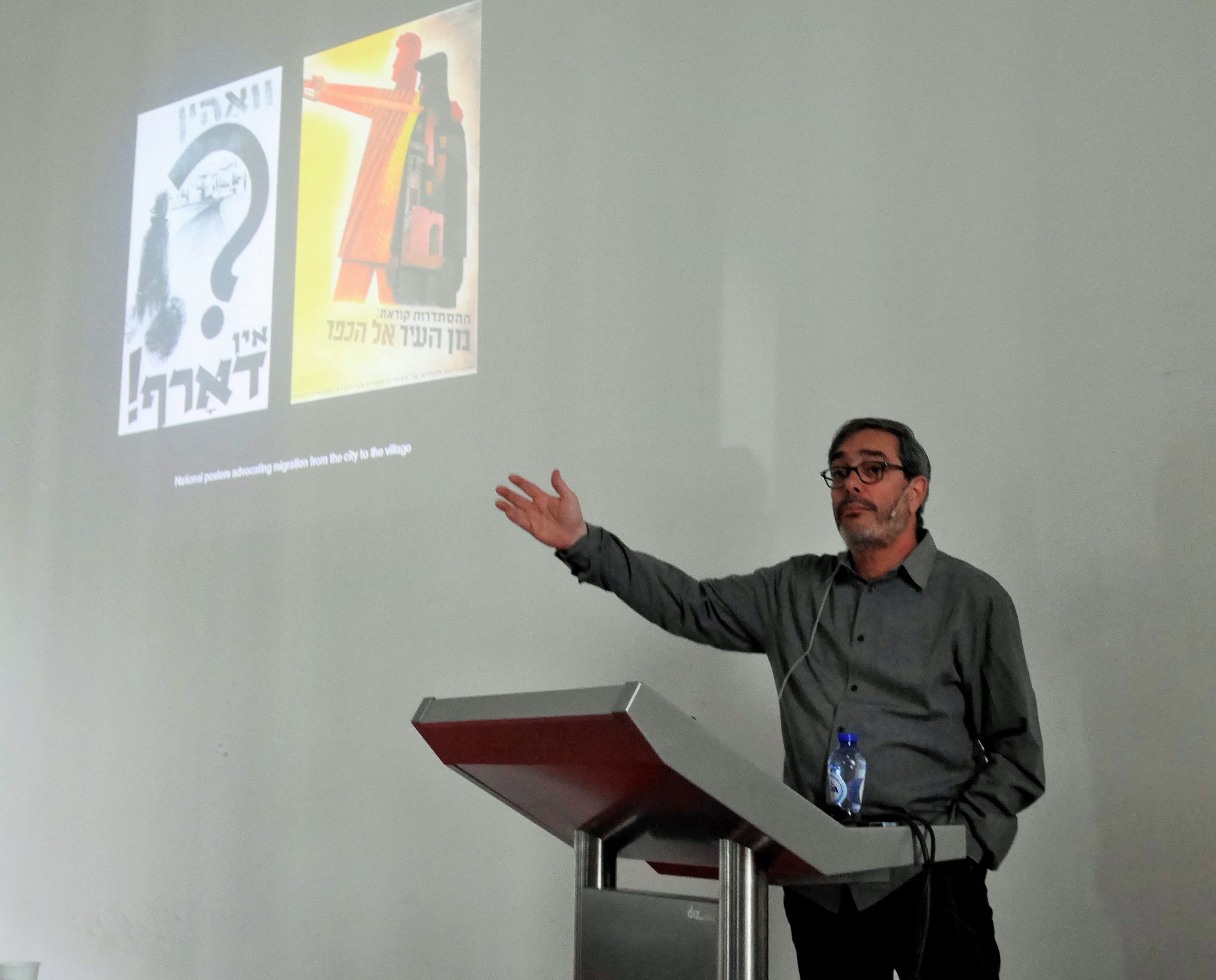

With the same title as Efrat’s 2004 book The Israeli Project, the lecture was held in the TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment. The lecture opened with footage of both Israeli state-building and Palestinian expulsion, and Efrat emphasised that, “the spatial invention of the state of Israel was enabled by this process of destruction.”

The Israeli state did not organically or gradually develop, rather it was engineered. Efrat described the Zionist project as transformative, totalising and anti-urban. As such, to avoid the ever-increasing population crowding the country’s small shore-line, planners subdivided the area into 24 regions which were equal in population. This process was greatly influenced by modernist and post-war ideas, such as German geographer Walter Christaller’s Central place theory, among others. Efrat described it as a “publically presented project of colonising and de-colonising”.

There was a particular focus on the building of new towns in the early years. Aside from any socio-political implications, Efrat commended the architectural feat of managing to continuously provide adequate housing for the incoming immigrants and refugees. The state owned most of the land, and new immigrants were shipped to these towns across the country, not necessarily by choice, to prevent the concentration of population. With the introduction of more neo-liberal politics in the late 70s the architecture of some old new towns changed and the policy of proliferating new towns continued, crossing now over the Green Line.

Efrat argued that some architectural problems in modern Israel stem not from disorganisation or a lack of forethought, but from extensive planning in the early years. Many of the new towns weren’t built because of strategic location or resources, but rather to fit the plan. There are few ‘ghost towns’ in Israel as consistent immigration fills the housing, and one audience member pointed out perhaps this incentivises little architectural reflection.

The lecture also examined the architecture of state buildings, which Efrat described as a physical manifestation of how the state wanted to represent itself. He pointed out how Brutalist architecture became strongly identified with Israeli culture, distinctly modernist and considered “direct, sincere, and expansive”. Buildings were distinctly modernist, absent of neo-classical over-tones you find in many state-buildings and by the 60s the country had become a “feverish laboratory of architecture.”

A complex intersection of politics, ideology, ethics and of course architectural innovation, the lecture can be watched online.

Comments are closed.