Ridding Namibia of acacia bush by turning it into marine fuel fairly, cleanly and sustainably would make many people happy. TU Delft researchers study this from all angles.

Namibia's safari landscape is disappearing. (Photo: Susan van der Veen)

Type in ‘acacia’ and ‘Namibia’ as search terms in Google and you will get post-colonial nostalgia: luxury resorts, safaris, sand dunes in the evening sun, giraffes nibbling on trees. Photos show windswept solitary acacia trees in a desert landscape. Beautiful wood too: red, strong, and heavy. But the reality is different: acacia trees may be beautiful, but acacia bushes are a huge problem.

Almost half the country is overgrown with acacia bushes. (Photo: Elisabeth van Rechteren)

Almost half the country is overgrown with acacia bushes. (Photo: Elisabeth van Rechteren)

Indeed, acacia bushes have got a bit out of hand in Namibia and, for that matter, in neighbouring countries South Africa, Botswana and Angola as well. Besides increasing drought due to climate change, overgrazing plays a role, as does the fact that farmers are burning shrubs as a management measure less than before. As a result, one third of the immense country is covered in acacia bushes. They surround pastures and the already low water table is sinking further and further. Researchers are talking about 45 million hectares covered by acacia bushes: more than 10 times the area of the Netherlands.

Acacia wood is converted into charcoal by burning it with a shortage of air. (Photo: Susan van der Veen)

The Namibia Biomass industry Group (N-BiG) has joined forces with public, private and academic institutions to tackle the problem plant. Clearing the acacia costs money and only works if there is revenue in return. So far, that mainly means burning the wood with little oxygen to make charcoal for export. This releases enormous amounts of particulate matter into the air, says PhD student Susan van der Veen (Faculty of Applied Sciences, AS), and working conditions are poor. “There is a lot of room for improvement there.”

This is the reason that Dr Lotte Asveld, a researcher in Biotechnology and Society at the Faculty of Applied Sciences (AS), visited Namibia earlier this year with several PhD students. Besides Susan van der Veen (Social and Sustainable Development), they were Sivaramakrishnan Chandrasekaran (Sustainable and Inclusive Value Chains for Marine Biofuel) and Elisabeth van Rechteren (master’s student in Life Science and Technology). The visit was part of the NWO Clean Shipping Project, a collaborative project comprising TU Delft research groups and industrial and social partners, that is looking into converting acacia into a sustainable marine fuel. Indeed, the merchant shipping sector has quite a challenge: a 50% CO2 emission reduction by 2050, while the expected growth of the sector is 50-250%. As sulphur and nitrogen oxide emissions also need to be curbed, biofuel would be a welcome alternative to crude oil.

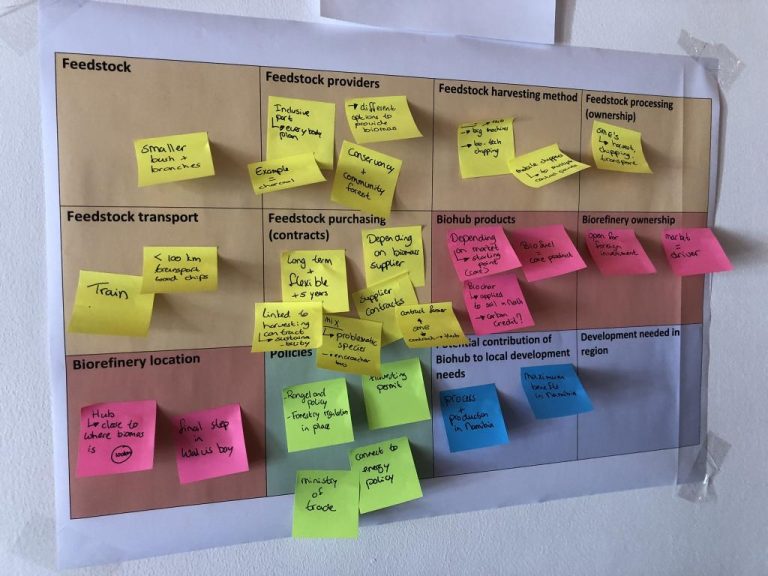

TU Delft researchers’ workshop with stakeholders. (Photo: Julian Nakanyala)

The Acacia Project will explore the possibility of converting acacia bushes into a marine biofuel in a local, sustainable and clean way. This is expected to improve farmers’ lives and create paid employment. It will involve farmers, local communities, biofuel producers, refineries, governments, aid organisations (NGOs) and buyers.

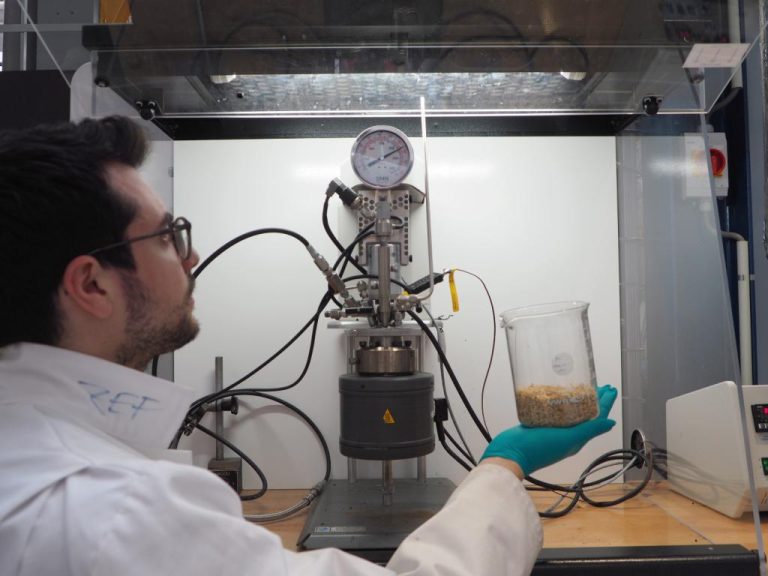

Nikos Bias converts wood chips into oil and gas, among other things, at a laboratory scale (Photo: Jos Wassink)

Nikos Bias converts wood chips into oil and gas, among other things, at a laboratory scale (Photo: Jos Wassink)

Back in the Netherlands, student Nikos Bias from Greece is working in the laboratory of the Department of Process and Energy (Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Maritime Engineering & Technical Materials Science, 3mE) on converting acacia chips into biofuel. Fine wood chips are heated to well above boiling point with water and a catalyst in a teapot-sized reactor. At temperatures of between 250 and 340 degrees Celsius, the pressure rises to between 50 and 150 bars.

At that temperature and pressure (hydrothermal liquefaction), the acacia chips disintegrate into four products in five to 60 minutes: bio-oil, biochar (a carbon-rich material), gas and water containing dissolved organic substances and salts. In the latest experiments, the bio-oil yield from 100 grams of acacia chips was 28 grams. The researchers hope to increase this a little more.

Dr Luis Cutz stores and examines several samples of acacia oil. (Photo: Jos Wassink)

The conversion Bias is working on was conceived and designed by Professor Wiebren de Jong (Process and Energy at Faculty 3mE) and Dr Luis Cutz (Specialist in Thermochemical Conversion of Waste Plastics and Biomass at 3mE). Cutz swiftly draws two axes on a whiteboard: horizontally the temperature, vertically the pressure. Dry conversions such as torrefaction, pyrolysis or gasification occur at low pressure. Wet conversions typically occur at lower temperatures but at much higher pressures of up to 200 bar.

Cutz has tested different techniques using various catalysts on the acacia chips. In doing so, he looked for the maximum conversion combined with maximum energy content. Cutz says that preliminary chemical analyses show that acacia oil is a clean fuel containing hardly any sulphur or nitrogen.

The Acacia Project is a jigsaw puzzle of parties and interests. (Photo: Susan van der Veen)

What next? Susan van der Veen is going to work out the interviews she has had with various stakeholders. She will use them to formulate proposals and conditions so that all stakeholders benefit from the conversion of acacia into marine fuel. Chandrasekaran, with his background in chemistry, has already started doing some calculations. He estimates that the annual additional growth of acacia (2% to 3% per year) could provide enough fuel for all domestic use as well as for export. He also sees opportunities for refining the acacia oil in nearby oil refineries in South Africa, for instance. The refineries could turn it into fuel for road and air transport. Processing acacia oil offers oil companies an opportunity to green their operations, notes Chandrasekaran.

TU Delft researchers head out into the field to interview people who are directly affected (Photo: Sivaramakrishnan Chandrasekaran)

The whole venture is a jigsaw puzzle of parties and interests, but with a clear goal: sustainable marine fuel from acacia bushes. When asked, Chandrasekaran estimates that a pilot plant could be up and running in Namibia within five years – if all goes well. Van der Veen sees that many parties are interested in it. “They would welcome it,” she says.

Meanwhile, Lotte Asveld is working on two tracks simultaneously for this project. She is seeking European funding for further research and is holding talks with unspecified interested companies. “For the next step, a pilot plant, we are looking for partners to invest in it,” she says. “Since the project looks so promising, I am confident that we will find them.”

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.