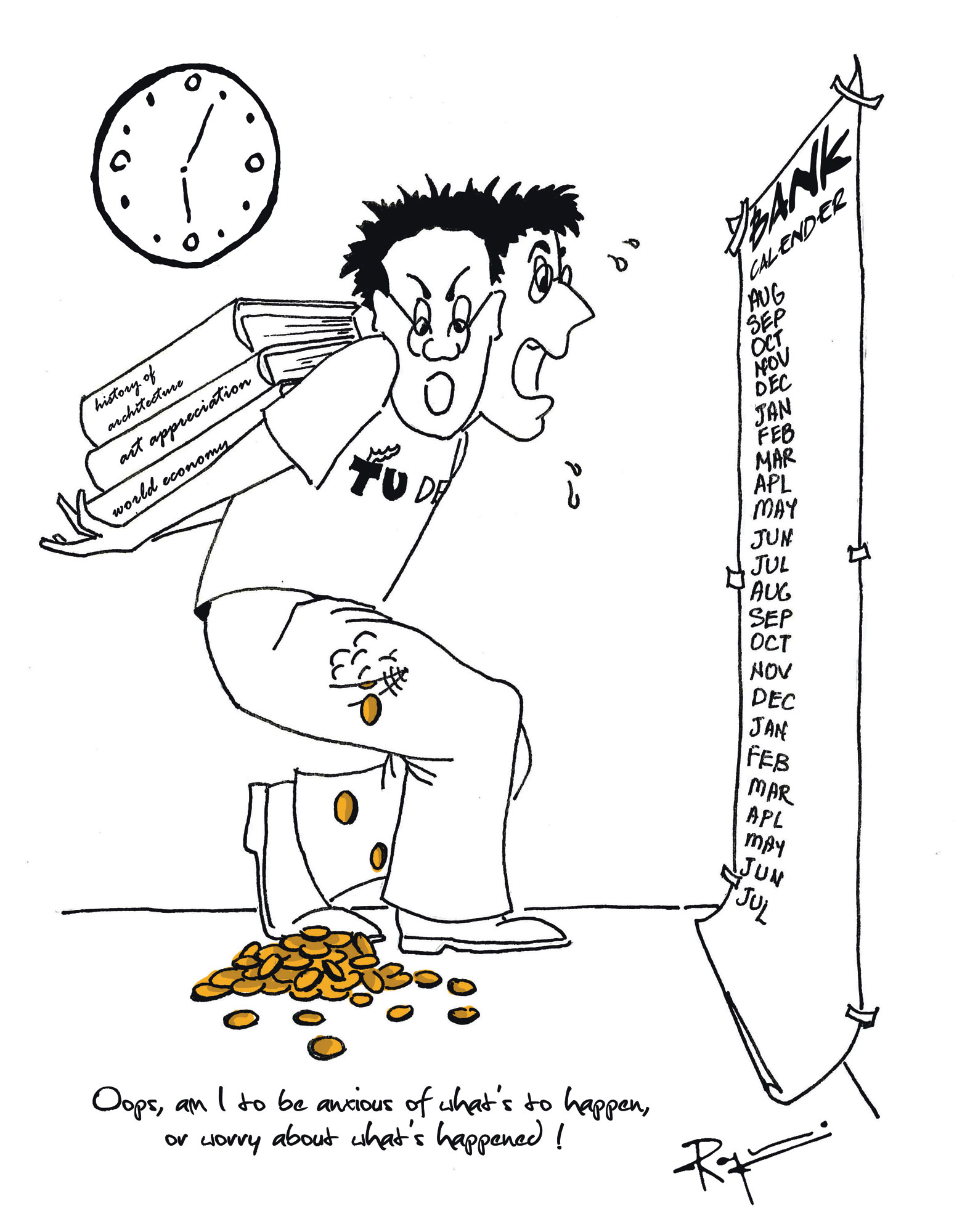

Making ends meet is no easy matter for many of TU Delft’s international students. Is the university aware of their struggles?

International students at TU Delft and in the Netherlands generally are worried about the ever-increasing costs of education in a climate of depressed global economies. Moreover, many international students are increasingly irked by the fact that their Dutch student counterparts pay as little as one-sixth of the tuition fee charged to non-European students. While it’s seemingly logical that the Dutch government views higher education as a business commodity, a tuition fee that is six times higher certainly seems excessive. The fact that most other European nations provide almost free education to both locals and internationals makes the situation even worse.

It is of course the international students’ personal choice to come to Netherlands in search of greener pastures, but once here, there are certain small matters which blow out of proportion when seen on a relative scale. For instance, this academic year, just two days before the deadline for renewing residence permits, a mail was sent out indicating that the costs of visa extensions had increased from €55.00 to €155.00. To get an extension at the old rates, students had to register within the next two days. It makes cynical students wonder why they’d have to cough up almost 200% more money if they had happened to miss that email for whatever reason? Minor issues like this trouble international students, especially when viewed in combination with other seemingly inexplicable factors.

A main problem, from the international students’ perspective, is that all the policymakers who frame key decisions are Dutch, and consequently seemingly ignorant of the workings of financial systems elsewhere in the world. Dutch employees, ranging lowly workers to executive directors, are all covered by a social security system offering comprehensive social benefits. The financial security enjoyed by these policymakers perhaps leads them to believe that the rest of the world also works in a similar manner. But thinking such is akin to living in a bubble, divorced from global realities.

Dutch university policymakers are no different from the rest in this respect, with study programs and course work designed in such a way to suit all students. However, the attitudes of coordinators suggest that they’re unaware of how things really stand for international students. They seem unaware of the fact that it’s almost impossible for non-European students to study a MSc program for more than 24 months, for example. Yet many international students finance their studies from several sources, and these sources usually fund students only for a stipulated period of 24 months. Conversely, it’s totally normal for Dutch students to study MSc programs for more than 24 months, owing to the various government subsidies they enjoy. Dutch students can also easily find part-time work during the academic year to cover expenses without worrying about delaying their studies.

David Reuijl, a Dutch Biomechanical Engineering student, says: “Working part-time was helpful for me, not just because of the money, but rather for the distraction from studies. It’s good to not study for one day a week. But international students have no way to take the going so easily.”

Reuijl also quickly adds: “I never encountered financial difficulties, but I do try to buy things as cheap as possible and like living cheap, because it makes me feel good”.

From the perspective of an Indian student, for example, matters are quite different. One euro equals 63 Indian Rupees, and a student can live like a king on 100.00 euros in India. To study at Delft, however, many Indian students must take out loans totaling around €35,000, at a staggering 14% annual interest rate. And when they return to India, they’ll have to work for around five years to repay this sum. Hence, such students literally cannot afford to take their studies as easily as many Dutch students do.

Exhausted

While the university organizes several orientation programs for students aimed at adapting to Dutch culture, it’s high time that professors and policymakers who directly influence international students get an orientation course, too. This orientation should focus on the ways international students differ from Dutch students in terms of financing, time constraints and set periods in which they must complete their studies.

The university committee must realize that the whole world doesn’t work on a financial scale comparable to the Dutch metrics. At TU Delft, one finds students from the richest of countries and wealthiest of parents, who come to Europe to simply experience the outside world, yet at the same institution there are many more students from much poorer countries and families who come to get quality educations that they can use back home to bring real changes to their societies. When eyeing an international audience to cater for its education market, the university must completely understand how financing works in different countries.

The unbalanced financial capabilities of international students and their Dutch counterparts results in varied spending patterns between the two. While the Dutch take regular summer vacations between the two academic years, for internationals such vacations are unaffordable commodities. Paying a staggering €750.00 tuition fee per month even while holidaying forces international students to work continuously for more than 24 months, by which time they’re totally exhausted by the rigors of 120 European Credit Points system.

To save a few euros here and there, international students do all they can, starting from shopping at cheap supermarkets to cutting down party nights and reducing their travel. But even these actions do not seem sufficient when they then see their hard saved money being siphoned off by other institutions, like the health insurance companies, the insanely over-priced university canteen, or the university’s Sports Centre, which charges its own students entry fees.

Bennett Cohen, an MSc student from the United States, suggests taking a cue from the American system: “US universities tend to be expensive, but you get everything for free once you’re in. There’s always free or well-subsidized trips and travel, and tremendous opportunities for career support. At TU Delft, it seems that most career services are almost exclusively geared toward the Dutch and many events and opportunities are communicated in Dutch or exclusively geared toward the Dutch as well. If the Netherlands is serious about becoming a ‘knowledge economy’, then international students need to be more welcomed to the higher education system.”

De nog ongemotoriseerde zwever werd tussen de twee rompen van het kunststof vliegtuig WhiteKnightTwo door vier motoren op 13,7 kilometer hoogte gebracht. Na loskoppeling zweefde het door Scaled Composites ontwikkelde ruimteschip ogenschijnlijk probleemloos terug naar het vliegveld van Mojave in Californie.

Uiteindelijk zal Spaceship Two niet alleen van honderd kilometer hoogte terug moeten keren, ook en eerst zal de commerciële spaceshuttle vanaf basishoogte met een eigen raketmotor tot honderd kilometer moeten klimmen, net als zijn kleiner voorganger SpaceShipOne heeft gedaan.

De techniek mag nog in ontwikkeling zijn, de commerciële ruimtevaart lijkt niet te stuiten. Virgin Glactic heeft al 370 mensen op de wachtlijst en over nog geen twee weken (22 oktober) wordt de landingsbaan van Spaceport America ingewijd.

Lees ook:

Gliding Spaceship brings space tourism closer

Comments are closed.